-

Meet the Teachers Series: Taking your DesignOps to the Next Level

Posted on

work·shop /ˈwərkˌSHäp/ noun: a meeting at which a group of people engage in intensive discussion and activity on a particular subject or project.

Instructors:

Kristine Berry, IBM Z DesignOps Program Director [bio]

Jenny Price, DesignOps Lead and Manager, IBM [bio]

Kristine and Jenny will be leading this workshop, Taking your DesignOps to the Next Level, starting Monday, August 29, 2022. We asked them to tell us a bit more about the curriculum beyond the standard website blurb (full description below). Here’s what they told us.

In a nutshell, what problem are you helping people solve at your workshop?We’re focused on uncovering how we might bridge the gap for teams who understand that DesignOps can increase the impact and effectiveness of their design teams but need to figure out how and where to focus those DesignOps resources for maximum benefit for the team and return for the business, and wider organization.

Who are those people, and why is it so important to them to solve it?

This workshop is for any DesignOps practitioner or manager who invests in design teams, whether they are just getting started or already have a dedicated team, whether they have a large or small design team, whether their design practice is emerging or mature, and whether they are looking to scale their capabilities at the organizational level. Understanding their biggest DesignOps gaps and pain points, finding solutions and creating a prioritized roadmap to bring back to their teams will help them take their DesignOps practice to the next level.

Does your approach represent a departure from previous approaches to addressing the challenge?

Our approach is unique in that we offer a quantitative and qualitative way to measure DesignOps strengths and weaknesses, and then we bring great DesignOps minds together to brainstorm ideas, opportunities, experiments and refine solutions while applying Enterprise Design Thinking practices.

Can you provide a brief anecdote/story about the problem/topic that illustrates it, and, ideally, your approach to solving it?

As one example, a design team set forth in defining performance goals for the year. The DesignOps practitioner had a “gut feeling” of where the DesignOps practice should focus but wanted to share data with the leadership team to validate this direction. They used the DesignOps assessment to generate a score for each of the four pillars we’ll be diving into during the workshop. Sure enough, one area of focus was validated (Yes, the team needs to work on defining better metrics) and a secondary one was highlighted (the role of design) that they hadn’t considered a priority before taking the assessment. This data was shared with the leadership team, who brainstormed solutions that they are executing together to address the biggest DesignOps needs of the organization.

Workshop Description

In this workshop, you will explore how you might build and scale essential areas of DesignOps to support sustainable design teams – whether you’re just getting started with DesignOps or already have a mature practice. Jenny Price and Kristine Berry, two IBM DesignOps leaders, will lead you through a framework (based on IBM Design Thinking) to assess your DesignOps capabilities and identify opportunities for growth. You will walk away with a customized, actionable roadmap for your team and organization’s path forward towards a sustainable and scalable DesignOps program.

During hands-on, team-based activities, you will assess and identify ways to improve your team’s DesignOps strategy by:

- Exploring strategies for advancing DesignOps within your team

- Assessing DesignOps opportunities and gaps for your team using IBM’s DesignOps framework

- Engaging with other DesignOps and Design leaders who are interested in solving for pain-points

- Developing a 30-60-90 day roadmap to share with your team

- Learning more about DesignOps resources, methodologies, and applications

Learn more and register here>>

Podcast: ADHD—A DesignOps Superpower

Posted on

The following article is based on a recent interview conducted by Lou Rosenfeld, Publisher of Rosenfeld Media from his podcast, The Rosenfeld Review. In this episode, Lou speaks with Jessica Norris, Design Enablement Coordinator. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

[Lou] My guest today is Jess Norris, Atlassian’s design enablement coordinator. Is that the same as design ops?

[Jessica] It’s part of design ops. At Atlassian, it’s one of our pillars regarding design ops. So enablement is really about programs focused on growth development and community. Something that we’re planning to look at first is onboarding. So how do we set up our new starters that are designers for success by aligning them with our best practices, the tool sets, and to what the expectation for what design quality really is?

[Lou] At the Design Ops Conference, you’re talking about ADHD and how it’s a design ops superpower. I’m really glad to hear this because I’m the dad of two kids who’ve been diagnosed with ADHD. There are a lot of different perceptions about what ADHD is in terms of, is it about hyperactivity? Is it about executive function? Is it about something else? Can you explain what ADHD is and then jump into how it impacts design and design ops?

[Jessica] Yes, definitely. So, going back to basics, ADHD is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. There are actually three different types of ADHD. The first type is primarily hyperactive and impulsive. That tends to be the stigma around ADHD, it causes hyperactivity. The second type is predominantly inattentive. So this is where I sit. And this kind of ADHD revolves around the trouble of regulating attention. So distractibility, or the difficulty of processing information quickly. And the third kind of ADHD is a hybrid of the two.

[Lou] Is there any correlation with gender? I certainly heard that boys tend to have ADHD of the hyperactive type, and girls are more likely to have the inattentive type.

[Jessica] I don’t know if there is a real correlation from a biological point of view, but ADHD goes severely underdiagnosed in women, and it’s because every single person with ADHD can present completely differently. Women also are very good at masking that they have ADHD. What I found is that in males, it can be more obvious, especially in children, if someone’s hyperactive. But for women, it can be seen as girls just being chatty, which is not as obvious. And apparently, the majority of studies on ADHD have been done on cisgender men. So that’s why a lot of what we know about ADHD is really skewed towards men as well.

[Lou] So, now that we have a general understanding of ADHD, let’s talk about your own experience. When you are hyper-focused, what do you tend to hyper-focus on?

[Jessica] I tend to focus on very detailed tasks. My background is in service design as well as product design. So working on journey maps, tasks that are really about problem solving and more detailed where it’s clear what you have to do. I just want to sit down and get it done already. That’s when I tend to be really focused.

[Lou] So let’s take service design. It sounds like you’re able to dig deeply into journeys, but do you have to step back to have the big picture of the journey, or a real broad understanding of the systems involved? Is that something you’re able to do despite the fact that it may not be at that level of detail? Or do you pair with someone who is able to sort of see that bigger picture, but may not be as strong at a detailed level?

[Jessica] I think everyone has their own strengths and so it’s very good to work in a type team because you really get to balance out those strengths and weaknesses. I do think that I can work at that high level picture. It’s just that I get more interested in the details. But I have a strong understanding of my ADHD. I’ve been lucky enough to go to therapy for it. So, I know how to pull myself out of hyper focus and how to have a really good baseline and regulate my attention more so I can be attentive to the stuff that is more high level that might not interest me as much. But it’s always good to be working within a team where you do have different needs and different strengths to balance each other out.

[Lou] On your journey to being diagnosed with ADHD, how did you find out you had ADHD and did it change the way you worked?

[Jessica] My journey to finding out that I had ADHD was quite long. I actually only found out that I had ADHD a year and a half ago. I had previous diagnoses of depression and anxiety and it’s so common in women to not get a diagnosis until adulthood. It definitely changed the way that I think about myself and helped me to really understand what my real strengths and weaknesses are. I know that there’s a lot of skepticism around ADHD. I had someone that I know say to me, “I don’t know why you’re talking about ADHD. It’s just putting a label on your problem.” And I think that’s partially true. But that label can really help you. If that helps you understand more about yourself and can help you really take control of your brain, why not? Why not add a label if it helps?

[Lou] Let’s talk about the design team setting and how you’ve been able to work with teammates in a way that plays well to your ADHD.

[Jessica] Yes, for my talk as well I was talking to lots of different people on my team and in my organization and the more that I opened up and spoke about my own experience with ADHD, the more I found that a lot of designers and a lot of people in design have ADHD or are neurodivergent in some way. So that could mean autistic or dyslexic as well. Some people can be a combination of all those things. For me, it was really clear to see design is an industry where people with ADHD can thrive. And that whole idea of neurodivergence actually means that we’re offering a unique perspective into design and into the world.

Every single person is different and has different needs. And I think that, whether you are neurodivergent or not, everyone brings a different perspective. I think one of the biggest things about the perspectives of people who are neurodivergent is there’s always going to be that empathy there, because anyone who’s ever been considered different from the norm, tends to really understand what it’s like to think and act differently. So they are able to really empathize with people who have diverse needs and diverse skills.

[Lou] So if empathy is one of the critical superpowers that ADHD people have, what else is a superpower when it comes to design ops? What perspective do you bring?

[Jessica] For me, I hyper focus under pressure. So, there’s a lot of times working in design ops where you need to quickly solve a problem and when you’re under that immense amount of pressure, people with ADHD tend to be able to go into hyper focus mode. I find that if someone sends me a message that says that something is urgent, I will drop everything, and put all my brain power into doing that urgent task.

[Lou] Let’s talk a bit about that one, because I can imagine that hyper focus is really valuable. But you could get 10 emails a day where the first word in the subject line is urgent. Does ADHD for you help you with prioritization so you can figure out which of those urgent tasks truly are the most urgent?

[Jessica] I think going to therapy as a result of ADHD has helped with prioritization. There, you are learning skills and strategies to really be better at work and in life.

[Lou] Anything else that you think ADHD people bring to design ops or could bring to it?

[Jessica] One of the biggest things that I’ve found with ADHD is it’s very commonly associated with a lack of dopamine, which is all about the pleasure and reward center of your brain. So, one really great way to get a hit of dopamine is to complete a task. So, if someone gives me a task, especially if it’s small and it’s something that I can do very quickly, chances are I’m going to do it straight away. I’m not going to wait around, because I really want that dopamine to hit. I want to feel a sense of accomplishment. I think that we’re very driven to actually complete something.

[Lou] So if someone is managing a designer or specifically a design ops person with ADHD, what should they know? What would you like them to keep in mind, with the caveat, that everyone is different with ADHD. And if they are a teammate of a designer with ADHD, would your advice be any different than for a manager?

[Jessica] Something that I’ve learned is that the things that help people with ADHD can actually help everyone in the team. I think that we always talk about the needs of the one and the needs of the many, but a lot of the time, if you address the needs of the one, it can address the needs of the many. One of the biggest things that has helped me is really giving timeframes to things to remove that ambiguity. If someone labels something as urgent, my brain goes into fight mode and wants to do it straight away. But if someone says to me, “this is due by the end of the day,” that’s a lot clearer for me and allows me to prioritize it within the scheme of everything else. We know that there’s always ambiguity in design ops, so you’re not going to have a specific detailed timeframe at all times but giving a rough guide can really help as opposed to just labeling something as ASAP.

[Lou] Thank you Jessica and good luck in that new job at Atlassian. We’ll see you in September. Thanks for listening to the Rosenfeld review, brought to you by Rosenfeld media.

Rosenfeld Media’s next conference is the DesignOps Summit, a virtual conference scheduled for September 8-9. Learn more at https://prod.rm.gfolkdev.net/designopssummit2022/

The Rosenfeld Review podcast is brought to you by Rosenfeld Media. Please subscribe and listen to it on iTunes, Stitcher, or your favorite podcast platform. Tell a friend to have a listen and check out our website for over 100 podcast interviews with other interesting people. You’ll find them all at RosenfeldReview.com.

Podcast: Standardizing Design at Scale with Candace Myers

Posted on

When it comes to design operations, it can be challenging to find the best method to provide the creative team with the tools they need that will eliminate some of their more mundane tasks to allow them more time to focus on their ideas and innovative work. Here, Lou talks with Candace Myers, design operations leader with Netflix StudiosXD, about how she integrates technology and practices to optimize her efficiency in the creative and design fields. Candace will be speaking at the DesignOps Summit 2022 virtual conference, September 8-9.

Candace recommends: Pivot Podcast with Kara Swisher and Scott Galloway. It has EVERYTHING that ops professionals needs to consider- human intent & emotion, business conditions, what good and poor leadership looks like, and brand strategy. It’s a must listen for anyone in tech, but especially generalists.

Read this podcast in interview form at Medium.com.

Podcast: Scale Your Organization and Grow Your Designers

Posted on

Lou sits down with the Head of Design for the Data Team at Amplitude, Courtney George, to discuss her talk “Scale Your Organization and Grow Your Designers” that she’s presenting at this year’s DesignOps Summit. What is a Design Leader’s role in providing stability for their team? How has that role changed over the course of the pandemic? Over the past few years, the security levels employees feel at their jobs have fluctuated drastically. Are there tools we are already using that can help our teams feel more confident in these uncertain times? Listen as Courtney and Lou touch on these topics, and more.

Courtney Recommends:

The Coaching Habit by Michael Bungay StanierCourtney Maya George is a design leader, mentor, mom of two, and a sketchnote hobbyist. She is currently the Head of Design for the Data team at Amplitude, where she’s building up a new product offering and growing the design organization. Prior to Amplitude, she spent nearly eight years at Adobe, where she built a design team from the ground up focused on the Developer Ecosystem.

She believes in creating an inclusive design culture and thrives on building relationships, solving complex and ambiguous problems, and coaching designers to take control of their own career growth.

Follow her on Twitter @courtneymaya and LinkedIn

Accessibility at Virtual and In Person Events

Posted on

The following article is based on a recent interview conducted by Lou Rosenfeld, Publisher of Rosenfeld Media from his podcast, The Rosenfeld Review. In this episode, Lou speaks with Darryl Adams, Director of Accessibility at Intel. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Welcome to the Rosenfeld Review. This is Lou Rosenfeld, your host, and today I am joined by Darryl Adams, the director of accessibility at Intel. Darryl, how are you?

[Darryl] Hey Lou. Thank you so much for having me today. Pleasure to be here.

[Lou] It’s great to have you join. We’re going to be talking about the issue of accessibility, especially at conferences. I’m certainly interested in it; and I know many of you are, whether you speak there, you put on conferences, you are conference producers, or you’re doing internal conferences. You know, in the days of Zoom, we’re all in the virtual conference business one way or another. I thought it would be great to have Darryl on. Darryl leads a team at Intel that works at the intersection of technology and human experience, helping discover new ways for people with disabilities to work, interact, and thrive.

Tell me a little bit more about your mission and your passion here. How does it connect to what Intel is about, and your background here?

[Darryl] Accessibility at Intel—there is a number of facets. One is the importance of making sure that Intel is a great place to work for employees with disabilities. We continue to try to drive an inclusive environment, but really getting down to an accessible environment for everyone. It’s always a long road, and that’s something that we are working toward. I think the key aspect, in my mind, around what accessibility really means for Intel is the future possibility of creating a future of technology that is fully inclusive and accessible for everyone, and really thinking from the beginning about how we create new computing architectures, new technologies that everyone can use. That is really what drives me specifically, and that comes from a personal space for me. I have retinitis pigmentosa. I’m legally blind, and losing my eyesight from the outside in. I’m also deaf in my right ear. These challenges have really shaped my perspective on working with disabilities, interacting with technology, how that can be a barrier, as well as a tremendous benefit. But we need to be deliberate in the way that we design technology in order to make it a benefit and not a barrier.

[Lou] Before we get into the conference side of things, I want to ask a little bit about that work at Intel. I always think a lot of people may be wrong that Intel is primarily a technology company. I also think a lot of accessibility is less about the design of the technology and more about the application of the technology and how it’s combined with design.

How much of your work at Intel is about impacting the way that the technology itself is created, versus how it’s applied?

[Darryl] Intel has a long history. Over 50 years of innovating computing and creating computer architecture. Think of it as the foundation of how we design. Today, if you are designing software, you’re designing software within some constraints around a 2D screen. You’re expecting an input from a keyboard or a mouse, and you’re building, innovating, and designing around that paradigm. And that computing architecture—that is the foundation of that experience—is a culmination of a lot of the work that Intel does under the hood and the work that we do across the industry, as well. We’re partnering with computer manufacturers, operating system vendors, that type of thing. My thinking here is that when we think about true accessibility, true user experience and user interaction with technology, it’s smart to start thinking about what we do beyond that standard computer interface we have today.

We have to think about this also along the lines of, if we look over time today, we are just a single plot point on a graph. But if you see that graph out, say, 10, 15, 20 years from now, computing power will increase exponentially. And the capabilities that will bring us, I think it stands to reason that we should be thinking beyond sitting in front of computers and typing, that type of thing, for our primary mode of interaction. And I feel that this is where we can come and think about new computing architecture and how we can evolve to take advantage of all the new capabilities that we see before us.

[Lou] And you’re reminding me that Intel’s in this position to create computing architectures, and obviously influence many other players in the industry. I imagine there’s a great amplification effect you can have by being right there at Intel thinking and talking about this issue.

What can be done to make [conferences] more welcoming and more inclusive for people to speak at conferences?

[Darryl] I think the conference context is broad. I really appreciate the question of how we make the conference experience for speakers more accessible. I think we’ve been having the conversation about how we do accessible conferences for the audience for a while now, and it’s important to consider the speakers as well. I would say that it all starts at the beginning. To me, we are always thinking about accessibility as being present from the very beginning, from the first conversations. When you’re planning a conference it’s not “plan the conference” and then figure out what we need to do with accessibility. It’s “plan the accessible conference from the start.” From the audience perspective that starts at the website and the approach that you take for registration ensuring that’s fully accessible.

Then, on the speaker side is ensuring that you are giving the speakers the opportunity to describe what they need in terms of an environment to be able to effectively engage. If we’re talking about a physical space and we’re at an in-person conference, it’s important to be able to provide access to the space and understand what technologies may or may not need to be used to support the speaker. Generally, I think that’s true for probably most speakers, but it’s really important because the devil is in the details on the nuance that somebody who is speaking, maybe with a disability. In my case, I can describe the example that visual impairment makes it very difficult for me to track anything visual. I can’t read a teleprompter, for example. Having to rely on visual cues is challenging at best. If I set my speaking engagement up where I am expecting very specific, non-subtle visual cues, and I don’t get it, then that becomes a problem. Having the ability to really go through the motions prior to the actual event is important. I think that also applies to the digital context as well.

[Lou] So, get to know the technology that’s at your fingertips, what visual cues you may be expected to know and if those aren’t working, how to replace them with alternatives.

Do you find that, besides seeing it in advance and having that type of orientation—as different events have a different flavor, voice, tone—is there any correlation between how formal the event feels and how much you are expected to present rather than discuss? Does that have any impact, or is that more an issue of personal style, regardless of accessibility issues?

[Darryl] I certainly think there’s a personal style aspect to that. This is also, maybe, a function of everyone’s personal journey with disability. With this level of disability for a long time, [I] have learned the tips, tricks, and techniques to manage it and be able to speak confidently with the tools that they have. I think a formal approach is fantastic. In many cases, and I think mine is one of them. My disability is progressive; I feel like I’m never really quite an expert with the tools that I have because I’m continuously needing to learn. That lends itself to probably a more casual style, more conversational. Then I think where I’m able to convey my ideas the best is through conversation rather than reading slides. I do think that while that is helpful for the disability context and for accessibility, it also probably should be true in general.

[Lou] Amen. I think this is sort of more, we could call it, casual. You could call it interactive. Maybe human is ultimately the way to look at it, but my gut is that removing pressures, like following a tightly organized script, reading slides, is probably better for everyone in every context.

Do you think an in-person conference organizer should be prepared not only to do the kind of orientation that you’re talking about, not just for disabled speakers, but really for all? It removes that pressure and makes people more comfortable, and supports remote speakers because something, I would imagine, that is a real benefit to disabled speakers is the option to speak remotely?

[Darryl] Yes. And that also actually does address one of the more technical issues around the transition of speakers. If you are onsite and maybe doing a transition from one speaker to the next, and the new speaker is going to use, maybe, a braille display or they’re going to have some integration with an earpiece where they’re listening to some audio cues or something like this, that’s pretty difficult to do. At least, it’s more time consuming than simply handing a mic to the next person. Those are challenges, but the ability to present remotely, it’s a great way to allow somebody to feel most comfortable in their environment and own all of the technology that they need to be successful.

The one caveat I would note here is that as much as my hardware, my physical devices are set up optimally for me, I don’t have control over the platform that’s being used, the software platform that the conference is using. Something I think is important to consider when you’re choosing the platform is choosing something that is going to be accessible for most people or, hopefully, for all people. Not all platforms are created equal, and some are much more difficult to interact with visually than others. That makes it more challenging, certainly from a visual impairment standpoint.

[Lou] Yeah. Our approach, generally, is to use platforms that are the most generic. A conference being produced, let’s say in Zoom, is familiar, obviously, to many people—speakers, organizers, and such—but also my gut [feeling] is that they’re more likely to have had rigorous accessibility studies performed than maybe more of a niche or boutique tool.

[Darryl] Yeah. Thinking about standard platforms that get a lot of usage is definitely a good starting point. I do think there is an additional piece to this. That is about how you use them. Zoom in particular is a simple platform, so that’s always good. The simpler the better, in my opinion. But then you need to know if you are going to go with automated captioning. Then you let your audience and your speakers understand that because that may be simple, and it is better than no captioning, you’re most likely going to run into some issues with the accuracy of those captions. If somebody is relying on captioning, that’s something to note, especially in thinking about the speaker. Generally, you’re thinking about captioning for audience purposes, but if you have a speaker who is hearing impaired and is trying to follow a conversation on a panel, for example, they’re also then going to be relying on their accuracy.

That’s an important thing to consider. Additionally, if you have a deaf speaker who is going to be using ASL interpretation, making sure that you have that flow well integrated in Zoom, ensuring that you’re pinning the interpreter correctly and that everybody has a great connection; because if you think about it, generally an audience or a speaker might have a little bit of tolerance for a poor connection for video as long as the audio is clear. But when you’re doing ASL, you really need to have a clear video connection to avoid issues with breaking up the flow of the conversation.

[Lou] Yeah. As an organizer, if you have any type of distributed actors, let’s say someone doing ASL here, a speaker there, I get nervous about lagging and what that could do to the whole flow. Not only for the speakers, but for the audience as well.

One last question from a speaker’s perspective. Is there any appeal to doing sessions that are prerecorded? We see in the virtual conference space a lot of conference producers have their speakers record, then they play the recording, and obviously it’s a very controllable type of thing. Then maybe they have their speakers join for a Q&A. We’ve resisted that; we like the live feel. It just feels more human, more normal, and has a bit of spontaneity; but I can see the benefit [of prerecording]. Would you say there’s a strong accessibility benefit for going with recorded talks?

[Darryl] I would say that there could be. But I also would more agree with you that the feel of a live conversation is preferable in that it is a more human experience for everybody involved. There is the downside of that, obviously, if you’re live and you’re unable to edit and redo. But that’s also maybe the reason why live is so much more compelling. I would encourage people—when given the opportunity—to do something live versus recorded to choose the live option. But I do see that mainly where that might come into play is with speakers who are new to being in the public eye and are a bit nervous about having only one take. But I don’t know in terms of disability or accessibility in general whether that’s a key issue. It doesn’t feel like it should sway one way or the other.

[Lou] The takeaway I have from this discussion about accessibility for speakers is—and I’ll take a page out of the accessibility book that we published by Sarah Horton and Whitney Queensberry, which is it’s really an accessibility thing first. If we think about accessibility…from the speaker experience from the get-go, it is a better experience for all speakers.

We’re going to move on to the audience, and what we can do by considering accessibility principles and design from the get-go, rather than applying it post facto and hoping we do well. Let’s start with in-person conferences. Most of us are pretty familiar with that experience, even if we haven’t had the opportunity to enjoy one for a couple of years now.

Are there any big items on the checklist for an organizer to consider for a disabled audience member?

[Darryl] Yes. I would say that first and foremost, the details matter. Every bit of the conference-goers experience should be looked at closely to understand where accessibility may be a factor or may need to be a factor. For example, arriving at a conference venue for the first time, what is the expectation for your audience? The first step is typically that you’re going to go to a registration desk. Does that registration desk support, and will they be able to support, people across the spectrum of disability? If somebody is blind, if somebody is deaf, if somebody is approaching in a wheelchair, do they understand how to assist those people appropriately? There’s a general need to be able to engage and support people where they are as they need it.

You must educate the frontline staff appropriately right from the start. I think getting that initial engagement is huge. If I go to a conference and I recognize that people are there, and they understand where I’m coming from as far as just being visually impaired and having a bit of a difficult time, maybe making my way around, that’s a really big difference. Otherwise, the feeling is I’m lost in a sea of people and maybe I’m fairly anxious about this because I don’t know where I’m going, not sure who to ask, that type of thing. Having that type of support system right at the front is a great start.

Is there any kind of audio mapping you’ve seen work? Almost like having an audio version of where to go? How to orient? How to navigate the space?

[Darryl] Yeah. Interestingly, we are doing some work at Intel with a company called Good Maps, which does indoor wayfinding, indoor mapping, primarily for people who are blind or visually impaired. This is fairly new technology that allows somebody to use their mobile device, very similar to how you would use the GPS in your car. You can plug in your destination, and it will give you step-by-step directions for how to get there. Then also provide points of interest along the way, if necessary. It requires the venue to be scanned initially, and then enable that service. I think it’s really promising because I think that it kind of addresses that key element of the unknown. It removes some significant variables. I think that’s maybe the name of the game here. How do you remove as many variables as possible for your guests? Make it very clear. In one sense, the indoor wayfinding or navigation system is fantastic. Coupling that with a kiosk that is a concierge type of thing where somebody can get full assistance that they need, regardless of what specific assistance that might be.

[Lou] I love that the technology is coming and that it doesn’t sound like it would be the hardest thing. Just a really good application of existing technologies. But, you’re talking about at the get go [going to] the registration desk. I wonder if it goes back even further, like signaling on a conference website. Often, the first place for an in-person conference venue selection is really challenging. As an example, we’re based in New York City. We do a lot of our events in New York City. It’s a vertical city, and it’s accessible in terms of public transportation. But then the venues themselves are often on multiple floors, and there may not be a whole lot of elevator capacity. Those are considerations as well, I imagine.

[Darryl] Absolutely. Elevators should be sufficient, but if there’s limited capacities, then that is an issue. But that would be something absolutely to be considered. To your point, for the pre-conference experience there’s a lot we can do to attract people with disabilities. Let’s say you’re deaf; you’re likely not going to a conference if you’re not sure whether or not there will be sign language interpretation available, or maybe that it’s limited. We pretty quickly think that it’s probably not worth the money and time to do that. If we turn that around and we start advertising more broadly about how we are supporting various disabilities, and we state very clearly that we’re going to have all sessions signed, as well as captioned and support for wheelchair access and visually impaired services, stating those explicitly and describing how we expect to support that, then we can start actually engaging people with disabilities more and making it more likely that they will show up at our events. It’s kind of “the chicken or the egg” problem. Today, I think a lot of events look at their audiences and, say, we don’t have a lot of people with disabilities that we need to make all these accommodations. The reason for that is because the event hasn’t historically been accessible to begin with. We need to get ahead of that and start really communicating and advertising to that disability community and then supporting them. Nobody does this perfectly. As long as we are deliberate about wanting to do this, and then learning from each experience, like learning what didn’t go well, addressing it, and creating new solutions for new events and growing over time, that’s the key.

What about at virtual events? Do you see that being a very different challenge for an organizer, considering attendees with disabilities?

[Darryl] A virtual event is going to bring far more diversity into the conference and event. I think it also eliminates a lot of those physical challenges. You don’t have to worry about the elevator capacity, but it also introduces new challenges. These challenges are more subtle, but probably have significant impact on the audience. An example would be if you are a blind user that uses a screen reader and you’re watching a session, if you have the chat enabled in the session, then what’s happening is you’re listening to that chat the entire time the session is going. If there’s something that’s creating a lot of engagement in the session and on the chat, then you are having to divide your attention between the speaker and this chat that’s coming through your headphones as well. That can be quite distracting. That’s something that’s hard to balance, but I think that giving it appropriate consideration to understand how best to manage that is something to be thinking about. I think there’s a few other scenarios where we have to be mindful of how we expect our audience to engage not only with the speakers, but with each other. This is difficult because depending on your own context or personality type or how you retain information, what works well for somebody will not work as well for someone else. It’s a matter of being mindful that we’re a collection of unique people with unique needs. We want to listen and respond appropriately, but it’s really important to understand where people are coming from, what they need, and try to address it as it becomes more apparent.

[Lou] That’s really interesting. I’m thinking about what you’re saying, and specifically in the virtual conference setting, this discussion is concurrent with the presentations in Slack. We have really high levels of audience engagement in Slack, and someone who is blind would obviously have a problem with that in terms of distraction. And that’s not just for people who are blind. There are many types of people who, for various reasons, might benefit from that. It’s another example of how being thoughtful about design for people with different disabilities opens up all kinds of possibilities for everyone.

Have you encountered people who are thinking about hosting a hybrid event, or maybe have some experience with hybrid events?

[Darryl] I think that this hybrid model is going to be the most challenging shift that we’ve seen since the pandemic began. The challenge is going to be more of a technology challenge. I think it is completely solvable, but we’re going to probably make a lot of mistakes along the way there. It’s really important not to underestimate the complexity and challenges around audio in a hybrid model. If you have a room full of people, or a room with people around a table, and then you have a number of remote participates, the audio in the room is always more difficult to hear when you’re on the line and you’re the remote participant. We need to think of ways that help resolve that. As an example, each of the in-room participants could have a mic of some sort. We’re testing these models in advance to understand how best to optimize everybody’s individual contribution.

It’s really distracting listening to a room that is echoing and people are talking over each and some people are loud, and some people are soft [spoken.] That’s in the best-case scenario. If you have a hearing impairment of any sort, you’re probably getting no value from that experience. Alternatively, when you are in the room, we have to make sure that we have an engagement model to visually remind people that there are participants that are not sitting next to them. We do this today with video technology, but this is another area where the nuance in the details matter. We need to come up with seamless models that we could display to remote participants when that’s appropriate to ensure they’re not being left behind, they’re being engaged, and they’re not an afterthought. If that’s the type of conversation that is happening, we need to just continue to maximize and optimize the audio in the room.

[Lou] Excellent point. Just to step back and summarize, let’s keep experimenting. You’ve made a really important point about being thoughtful from the very beginning. A really important point in design in general is that thoughtfulness is important for all audiences.

Is there anyone or anything that you’ve been learning from lately that you want to shine a bit of light on?

[Darryl] We have a book that we typically recommend to Intel folks when they’re just starting their accessibility journey or need to learn and understand more about disability. The book is called Demystifying Disability, and it’s by Emily Ladau. I really can’t say enough good about it. It is a book that is simple to read or listen to, in my case. It gives you the vocabulary and the tools that you need to have in order to have respectful, engaging conversations with people with disabilities. It really opens the door to the whole community and gives a really nice overview and understanding of a lot of the differences and complexities that we have to navigate. It’s a fairly short read, but you are guaranteed to gain some valuable insights from it.

[Lou] Well, short reads are the best reads demystifying disability by Emily Ladau. And Darryl, thank you so much. Great discussion again. I wish we had a little bit more time. I’ve been speaking with Darryl Adams, Intel’s director of accessibility.

Rosenfeld Media’s next conference is the DesignOps Summit, a virtual conference scheduled for September 8-9. Learn more at https://prod.rm.gfolkdev.net/designopssummit2022/

The Rosenfeld Review podcast is brought to you by Rosenfeld Media. Please subscribe and listen to it on iTunes, Stitcher, or your favorite podcast platform. Tell a friend to have a listen and check out our website for over 100 podcast interviews with other interesting people. You’ll find them all at RosenfeldReview.com.

New workshops now open for registration!

Posted on

Podcast: Making Conferences More Accessible with Darryl Adams, Intel’s Director of Accessibility

Posted on

With the surge in popularity of, and need for, hybrid and virtual events, Lou sits down with Intel’s Director of Accessibility, Darryl Adams, to discuss how technology can make in-person and virtual conferences more accessible and inclusive to speakers and audience members with disabilities. He also speaks to how accessible conference design can be improved and fine-tuned for speakers with disabilities, and help those without disabilities feel more comfortable presenting. What kind of accessibility principles and design factors should conference hosts consider for audience members with disabilities and those without disabilities when setting up for in-person and virtual events? How does this technology increase engagement and diversity in attendance? Listen as Darryl and Lou touch on all these topics, and more.

Darryl recommends: Demystifying Disability by Emily Ladau

Darryl Adams is the Director of Accessibility at Intel. Darryl leads a team that works at the intersection of technology and human experience helping discover new ways for people with disabilities to work, interact, and thrive. Darryl’s mission is to connect his passion for technology innovation with Intel’s disability inclusion efforts to help make computing and access to digital information more accessible for everyone and to make Intel an employer of choice for employees with disabilities.

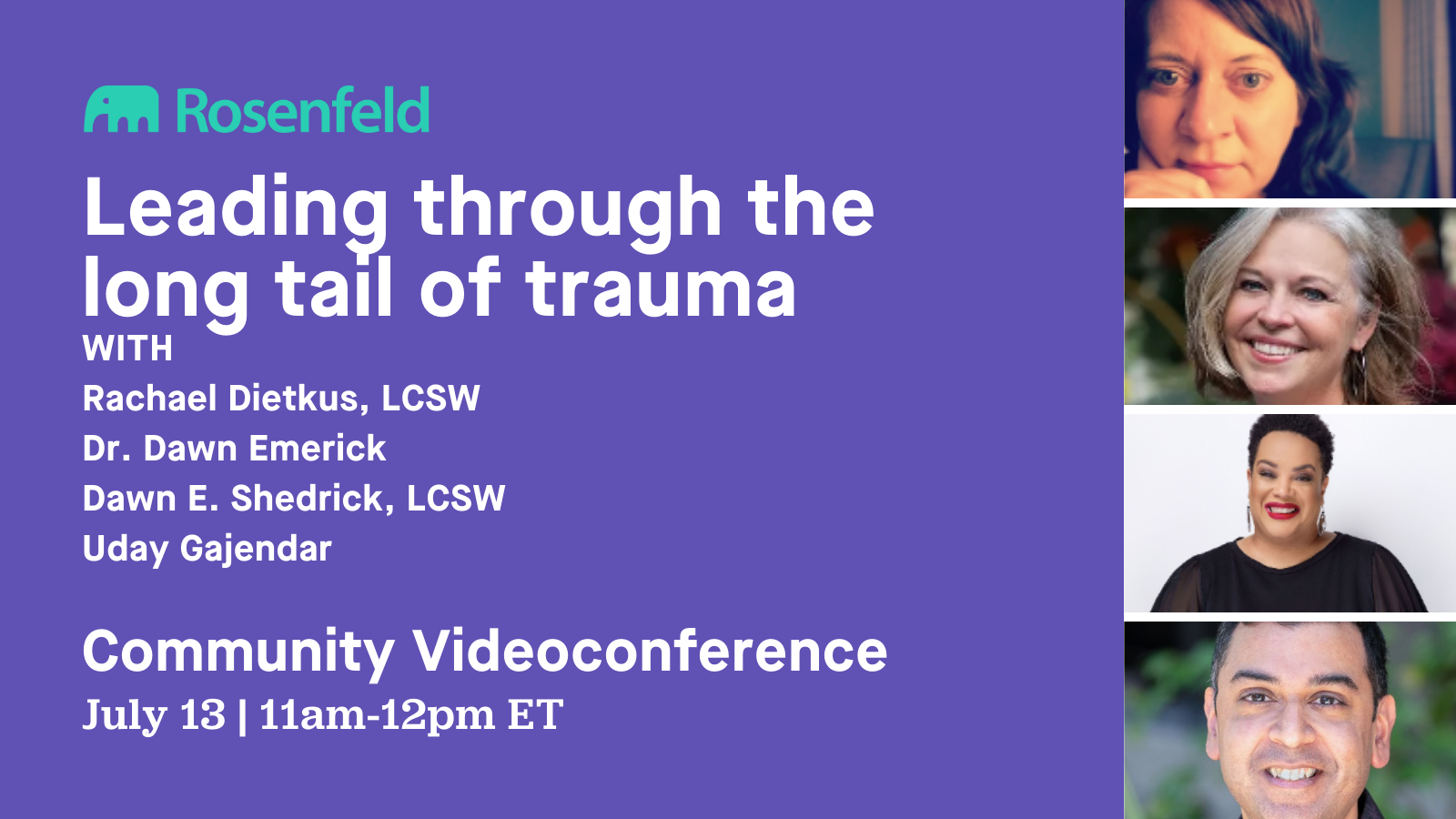

Community Videoconference: Leading through the long tail of trauma

Posted on

Please join our free Advancing Research community or Enterprise Experience community for access to the recording. You’ll receive a welcome email with a Dropbox link to our archive of past calls.

The fatigue and trauma from events of the past few years has affected many of us – not just personally, but also professionally, and at the organizational level as well. For the most part, the corporate world has recognized the impact these past years have had on employees and teams. However, many organizations have only recently become aware of the longer-term effects and are struggling to support their people as they work through the long tail of trauma

In this special community call, produced in partnership by Rosenfeld Media’s Advancing Research and Enterprise Experience curation teams, Uday Gajendar will facilitate a discussion about the long tail of trauma, with Rachael Dietkus, LCSW, Dawn E. Shedrick, LCSW, and Dr. Dawn Emerick.

They will cover:

• What it means to be a “trauma-informed leader”

• Ideas to keep in mind when handling stressful/anxious events or circumstances with your team

• Differences in supporting people during an event and its immediate aftermath, vs in the long tail of trauma

• Specific actions you can take with your teamPlease register to join us via Zoom on July 13th at 11am ET and learn more about the long tail of trauma, how it can affect your organization, and what steps you can take toward a sustained and intentional strategy for leading your team through long-term, post-pandemic challenges. The panel will be recorded, but we will turn off the recording for audience Q&A.

The speakers:

Rachael Dietkus, LCSW

Rachael is a macro-focused clinical social worker focusing on trauma-conscious practices in design. She is the founder and Chief Compassion Officer for Social Workers Who Design, a consultancy focused on integrating ethical understanding and trauma-conscious approaches in design. She is a two-time alumna of UIUC, where she studied Sociology and Social Work.

Dr. Dawn Emerick

Dr. Dawn Emerick is a speaker, trainer, and coach, focused on trauma-informed leadership. She’s a LinkedIn Learning instructor, a 2021 TEDx Jacksonville speaker, and host of the Leadership Uncensored podcast. Over a span of 30 years, she crafted her leadership, organizational development, and engagement skills at various private, government, and non-profit organizations in Florida, Minnesota, Washington, Oregon, and Texas.

Dawn E. Shedrick, LCSW

Dawn Shedrick, LCSW-R, is the founder and CEO of JenTex Training & Consulting, a professional development company that offers continuing education training; leadership development training and coaching; and consulting to the human services, healthcare, and social justice sectors. Dawn has also designed and delivered mental and emotional wellness and LGBTQ inclusion seminars in corporate workplaces including Travelers Insurance, JP Morgan Chase, GE, The NY Mets, Office Depot, GlaxoSmithKline, National Grid, Columbia University, and Canon USA North American Headquarters. She has delivered trainings to in-person audiences throughout the United States and abroad in Canada, Puerto Rico, Tanzania, and China and has created interactive virtual learning events for global audiences.

Uday Gajendar (Co-curator, Enterprise Experience Community)

Uday is a Design Manager for Aurora Solar who specializes in next-gen innovation projects and “three-in-a-box” product development with business and engineering leads. He also regularly writes for ACM Interactions and speaks worldwide on design topics at SXSW, UX Australia, IxDA, Midwest UX, and other venues. You can read Uday’s thoughts on design at his blog and on Medium.

A Guide to Success for Content Designers and Strategists

Posted on

The following article is based on a recent interview conducted by Lou Rosenfeld, Publisher of Rosenfeld Media from his podcast, the Rosenfeld Review. In this episode, Lou speaks with Natalie Marie Dunbar, author of From Solo to Scaled: Building a Sustainable Content Strategy Practice, just published by Rosenfeld Media. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

[Lou] Welcome to the Rosenfeld Review. I’m your host, Lou Rosenfeld. I’m very happy to have today’s guest, Natalie Dunbar, author of the newest Rosenfeld Media book, From Solo to Scaled: Building a Sustainable Content Strategy Practice. Now, Natalie, first of all, welcome.

[Natalie] Thank you, Lou. Thank you for having me. I’m glad to be here.

[Lou] So we’ve talked about this topic before. I know it sounds to people listening like it might be somewhat technical. And actually speaking of engineering, well, really maybe architecture, you’ve got a lot of construction metaphors throughout the book visually as well as textually. And yet when we talk about this subject, a lot of it kind of boils down to how someone is feeling about the prospect of building a content strategy practice and building one that’s sustainable over time.

Why is this more of an emotional topic than I had expected?

That’s a great question. I think in my experience, and experience of people that I’ve spoken with while writing the book, the process can be lonely. If you are a solo content strategist attempting to build a practice, you’re by yourself as the lone content person in the room and you’re trying to figure out who the people are that you can talk with that will help in understanding what it is that you’re trying to build and then come alongside you when you’re building it.

If you’re leading a team in a larger organization, you may be interacting with levels of leadership that you may not have had to interface with on a regular basis. And all of a sudden you’re like, “This is how we’re going to do it. This is the process. These are the things that I need. This is the resource that we need.” So I think having a companion and a guide surfaced as I kept hearing, I wish I had a narrator or a guide telling me, “Okay, take this step. Take this step.” And then to step back and take a breath before you move on and keep pushing. I think that’s where the emotion comes in.

Have you found any inspiration or lessons from the growth of design practices that’ve been useful for you as you’ve tried to work your way through building content strategy practices.

I don’t want to simplify the ways that design has come to this place of being at that product development table with the developers and everybody else. But I’ll say that I think as content strategists and designers, we’ve got the seat at the table and we’ve also started building our own tables. It depends on how your organization or agency is set up. You may be seated at the table with people, or you may have your own table and people are coming like I said to sample whatever you’ve got there. What I’ve learned over the years is how to speak the language of all the various cross-functional teammates. There’s a whole chapter in the book about how important it is to build alliances. And that’s a theme that runs throughout the book. This is not something that you do in a vacuum.

I made the rookie mistake early on of going into an agency like I’m here to save the day. I hadn’t really thought about the fact that I was the first content strategist at that agency. So everyone was asking me, what exactly is it that you do? I was talking about things that the team had already done and after a couple of weeks of back and forth and not really having any forward motion, I thought, okay, so let’s start again. Let’s sit down and figure out where does the product development cycle begin? How does it kick off and how much lead time do we need? So, from that, I remember sitting in a conference room that had whiteboards all the way around. Lots of markers, lots of post-it notes. And we created a process framework and figured out where are those crucial handoffs. And at every moment that we identified another cross-functional teammate, it was like… How can I speak to that teammate? How can I speak to a designer? I can use design thinking language. I can use service blueprint language. I can use different language that helps everyone understand what it is that I’m trying to do as a content strategy.

Are you having to be the one who learns that language everywhere you go?

Yes. There’s something that I call the “Persistent Principles” that I wrote about in a book and one of the very first ones is “Always Be Educating.” So even when your practice is established, someone new is going to come along, a new developer, a new IA, a new designer, and they’ve maybe never worked with a content strategist or content designer before.

Maybe they’re used to tossing designs over the proverbial fence and asking for the words to be plugged in instead of the other way around, which is particularly difficult in highly regulated spaces. Insurance and healthcare, in particular, you’ll have this lovely design and then the content breaks that design because it’s required. And then there’s this big kerfuffle and we’ve got to start over again.

How does “Building a Sustainable Content Strategy Practice” get started? How do you build? How do you scale?

So the steps of building the practice are going to be the same, whether you’re solo or building with a small team. I’ve provided a blueprint called the “Content Strategy Practice Blueprint.” There are five components to that blueprint and they include making the business case, building strong relationships with cross-functional teams and departmental partners, creating frameworks and curating tools to build with right-sizing the practice. So now we’re talking about starting to scale the number of people or practitioners. If you’re at an agency like I was when I built my first practice, that might mean bringing on contractors for a specific client relationship that you have.

And then the final component in the blueprint is establishing meaningful success measures. We’re talking about what are the practice OKRs? What are the goals of the practice? Not at the project level, but at the practice level. And once you have gone through those steps, that’s when you step back and you look at those success measures and you say, “Have I been able to meet these goals that I told leadership that I was going to?” And, “Do I need to go back through any of these steps and shore things up?”

Then you can decide if the structure is healthy enough for us to start scaling. That’s where the growth happens. That’s where, if you’re at an agency, maybe you’ve established yourself as a solo practitioner and you don’t need more bodies, but you have people coming in as contractors as you are bringing on clients who are establishing this demand for the content strategy work to happen.

Within an enterprise, that might look like all of a sudden, more and more teams are asking for content strategy expertise. And all of a sudden, your project list is growing, and you need to bring in more people and more practitioners. There’s never anything that’s really basic about a content strategy project, but there are some where we’re going to launch this new feature. We need content. We need copy. But we also need to figure out, where does it live on the site? What’s the nomenclature that we’re using? Is it consistent with other topics that might be similar on whatever digital experience that we’re building in?

I think this is a good point, as you’re looking at bringing in and scaling your practice, to look around your product table. Look around the practice that you’ve established and consider the importance of bringing in a diverse team. When you start to diversify your practice team, you’re going to start to hear different perspectives. And then that will broaden your reach as your audience starts to grow.

Let’s say you have a 15-person practice. Is there like any type of ideal ratio of UX writers to information architects to something else?

Ideally, we would have all the above embedded into product teams. That’s a tricky question because there are so many names that we go by. I’m a purist. I stayed with content strategy because that’s how I learned it and that’s what I know. But I also have worked in roles where I’ve been a content designer. I’ve done IA work. I’ve also been on teams where I was the strategist. I figured out the strategy and handed it off to a UX writer.

So now we’re talking about diversification of skills within a content strategy practice. Your practice may include only people who produce content, but you may find that in order to scale, you need to consider what Ann Rockley refers to as your “frontend and your backend content strategist.” So, your people who identify more as a frontend – I like being in the research. I like the closest I can get to the user, or the audience that we’re creating experience for. That’s my happy place. And then someone who is more than happy to sit down with developers and engineers who is perhaps more comfortable working on the backend. So, as you scale, you might find that in order to continue to sustain a healthy practice, you need to diversify in those specialties within content strategy.

I think it’s good that you’re also framing them, not as roles, but more specialties or skills. Would it be safe to say that if you’re building that practice, you have to hire people that are ultimately willing to wear different hats? They may have their comfort zones, their happy places, but ultimately, it’s a new enough area that sometimes in a given day, one of your people might have to be doing Ann Rockley’s frontend work, another day backend work?

That’s right.

Is that still the case even in a mature content strategy practice?

Yeah. I did a fireside chat recently about the fact that there’s so many specializations within the content world. And it really boils down to understanding what it is that I think that you are passionate about. And also being very honest about what areas I am passionate about. For example, content modeling is still a world of wonder for me. If I don’t have anyone else on the team, then I have to do it. And if I get a little stuck, maybe there’s an architect that I can confer with on a previous job that I was on.

I sat down with the project manager, who had passion for the backend piece of content strategy. He walked me through a couple of examples and all of a sudden, I’m doing content monologue documentation. So just be open and get out of your own way. Certainly, if you are more comfortable with certain aspects of content strategy, don’t try to shoehorn yourself into something that you’re ultimately going to get stuck. But instead of immediately fleeing from a different job, see it as an opportunity instead of a weakness.

There’s so much to developing a content strategy practice and I know we just really scratch the surface here, but I’m really glad that those who are overwhelmed by it, including myself now have a handy guide, From Solo to Scaled: Building a Sustainable Content Strategy Practice. It’s been delightful to spend time talking with you about it.

From Solo to Scaled: Building a Sustainable Content Strategy Practice is now available from Rosenfeld Media.

The Rosenfeld Review podcast is brought to you by Rosenfeld Media. Please subscribe and listen on iTunes, Stitcher, or your favorite podcast platform. Tell a friend to have a listen and check out our website for over 100 podcasts with other fascinating people from the UX community. You’ll find them all at RosenfeldReview.com.

Excerpt: Chapter One of our Newest Title, From Solo to Scaled by Natalie M. Dunbar

Posted on

Chapter 1

The Content Strategy Practice Blueprint

I’m fascinated by buildings: single family structures, high-rise dwellings, and especially office towers. As such, I’ve always had a healthy curiosity about the construction process. For example, Figure 1.1 shows a Habitat for Humanity building that I worked on. From the initial breaking of ground to the completion of a building’s façade, I find comfort in both the art and order of construction—how foundations support columns, columns support beams, and beams support floors. When the building plans are followed as written, every element comes together perfectly to create a strong structure that is capable of withstanding natural elements like wind and earthquakes.

In my career as a content strategist, I’ve heard colleagues speak about “standing up a team,” or “standing up a practice.” There was familiarity in the concept of building a figurative structure that had a specific function or purpose. And, of course, that familiarity stemmed from my fascination with buildings, so the construction metaphor made sense to me.

That metaphor also reminded me of one of my favorite books, Why Buildings Stand Up, by Mario Salvadori. Before writing and content strategy became my full-time job, I worked in various roles in residential and commercial real estate. All of those roles exposed me to various phases of building construction and tenant improvements, and reading Salvadori’s book helped me understand construction and architecture in an engaging way.

The familiarity I felt when hearing the phrase “stand up a practice” in the digital experience world often stopped short of the idea of the building metaphor. For example, practices were “stood up” with no attention to order. Foundations were poured before soil tests were completed, often resulting in skipping the addition of the footings that might be needed to support the foundation, or in the case of the practice, doing the work to ensure that the practice followed the necessary processes to create digital experiences that met the needs of users as well as the goal of the client or business. And inevitably, the structure—or the practice—began to crumble.

And sometimes those practices failed completely.

From the Ground Up

Having had the opportunity to build an agency-based content strategy practice from the ground up, and later expanding and maintaining an existing practice within a mid-to-large sized organization, I began to see that failures often happened because steps crucial to supporting the structure had been skipped. Or perhaps the structure had been compromised because the framework used to build it—if one was used at all—couldn’t withstand the constant stress of tension and compression.

When I started to think about what caused these seemingly strong practices to crumble—I returned to the building and construction metaphor to look for possible answers. That’s because it’s sometimes easier to, er, construct a mental model that’s more tangible than the nebulousness nature of digital information spaces.

If the building metaphor still feels a bit weird to you, then try this: think of the last time someone asked what you did for a living. If you’re a UX practitioner, or if you collaborate with members of a UX team, you’ve likely experienced the feeling of the listener’s eyes glazing over as you tried to explain the concept of user experience—or as I once saw it described, “making websites and apps stink less.” Then think of what might happen if you described the user experience using a more relatable metaphor, such as one of the following:

- The internet is a space.

- A website or mobile app is a destination within that space (and in the case of websites, a space complete with its own address).

- The work you do helps people avoid getting lost in that space.

In keeping with this theme, now imagine that the opportunity that’s immediately in front of you—that of building a UX-focused content strategy practice—is a pristine plot of land. Provided you have a solid plan and the right materials and tools, this untilled soil is ready for you to break ground and to stand up a healthy content strategy practice.

So this figurative plot of land you’ve been given needs someone—you—to till the soil and prepare the space for a structure to be built. And the creation of the plans for that structure, as well as sourcing the building materials and the tools you’ll need to build it, has also fallen to you.

Lucky for you, this book is your blueprint.

To continue reading, order your copy of From Solo to Scaled!

News & Announcements

The latest from Rosenfeld Media