-

What we learned from our AMA with Indi Young: a Recap

Posted on

During our “Ask Me Anything” with Indi Young, author of Mental Models and Practical Empathy, we touched on subjects ranging from opportunity maps and research repositories to Jobs to Be Done and empathy as a design concept. Read on for a recap of the session, and please join our Slack here to stay informed about when our next #rm-chat author AMA will be!

During our “Ask Me Anything” with Indi Young, author of Mental Models and Practical Empathy, we touched on subjects ranging from opportunity maps and research repositories to Jobs to Be Done and empathy as a design concept. Read on for a recap of the session, and please join our Slack here to stay informed about when our next #rm-chat author AMA will be!

Q: I’m wondering if you have any thoughts to share about using empathy as a concept to design for not just people but also the environment or any larger system. -Behnosh N.

A: I have used it and seen it used for designing systems for people, but not environmental ecosystems. Several government digital offices are using my approach to understand people more deeply, to see the differences in approach, to see different thinking styles … and to think in the problem space so as to discover people they’ve ignored.

Q: I’m curious about using the thinking styles approach in developing key archetypes within a body of population health research. Often, patients tend to get heavily sorted by demographic characteristics because they map to certain physical and social determinants of health conditions. But these don’t go far enough to capture attitudes, beliefs, behaviors etc. How have you used the thinking styles frame for rather large and diverse populations? – Jeremy B.

A: What I’ve done is framed several studies by “a person’s purpose.” Often, with health, their purpose is to “cope with,” so for example one study was “coping with my three ongoing conditions.” You must frame by a person’s purpose, so then you can get deep. (either in solution space or in problem space). You can go deep in listening sessions where you help the person trust you and get into their inner thinking, emotional reactions, and guiding principles as they were pursuing this purpose. Here’s my course on listening deeply.

Q: Research ultimately is about learning what we don’t know. Often we’re so focused on who our customers are that we forget that the real work in understanding how we’ve lost or who we’ve failed to win.How do you find, recruit, and drill down to the why of those who were near loses or recent loses? – Arpy. D

A: I would like to see us quit measuring by “engagement” altogether (“hey, someone looked at me through this glass pane!!”) and start measuring by how well we support each thinking style within each slice of their mental model toward accomplishing their purpose. I encourage people to do listening sessions with stakeholders, over and over, like monthly with each stakeholder at first, to develop rapport and trust. But you could totally make thinking styles if you do enough of them!

A: “Repository” as a neutral word … that’s needed. My opportunity maps are research repositories in visual form. But “repository” as in a software product … I’m very wary of those. A file system with folders, or Slack, or Basecamp … those ought to work. Truly, what it takes is the team to engage on it. A tool won’t do it. Equally, I distrust the software tools that claim they can go through your data and analyze it. Nope. I’m not buyin’ it. I spoke to a guy very involved in AI and speech understanding a year ago, and the best example is STILL KEYWORD RECOGNITION. Hah. That will not bring understanding. Keywords <> sarcasm, irony, laughter, hesitation, depth…

Q: Is there a place where we can find examples of opportunity maps and read about use cases? – Jess

A: Best bet is on my site, and even better bet is my course on using mental model diagrams as opportunity maps.

Q: Jobs to Be Done intersects with much of your work. Your Thoughts? – Scott. W

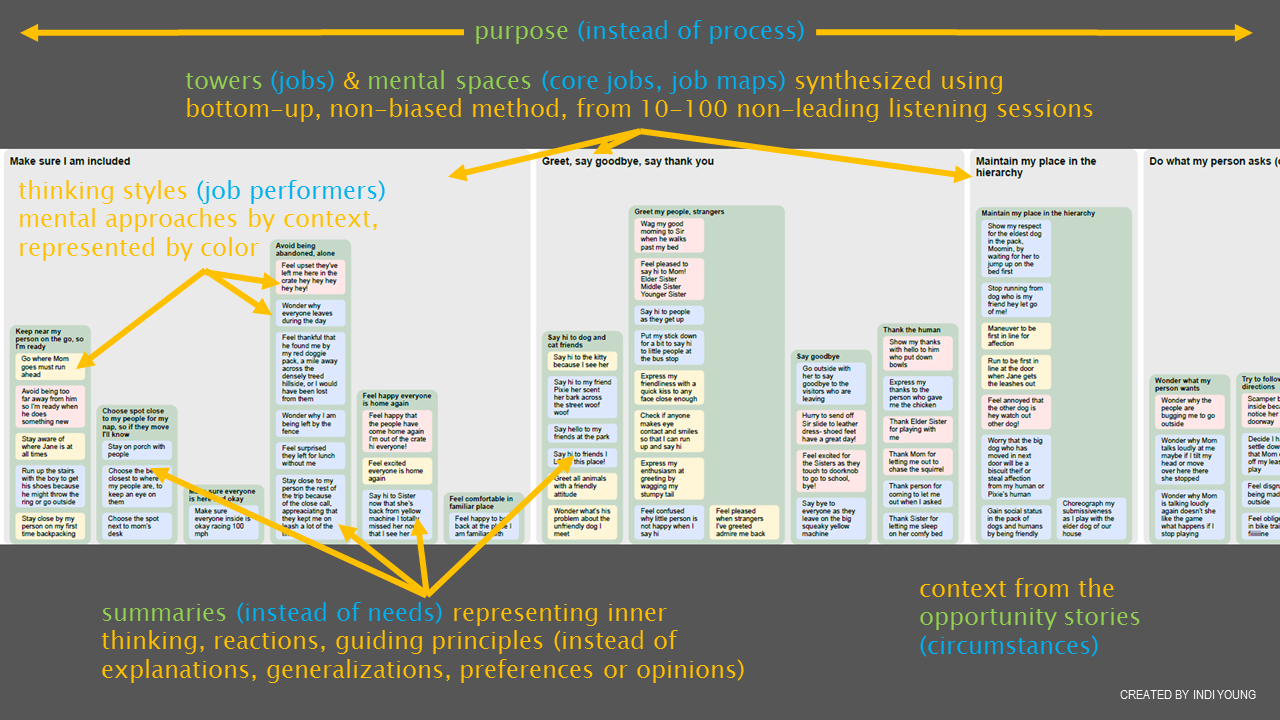

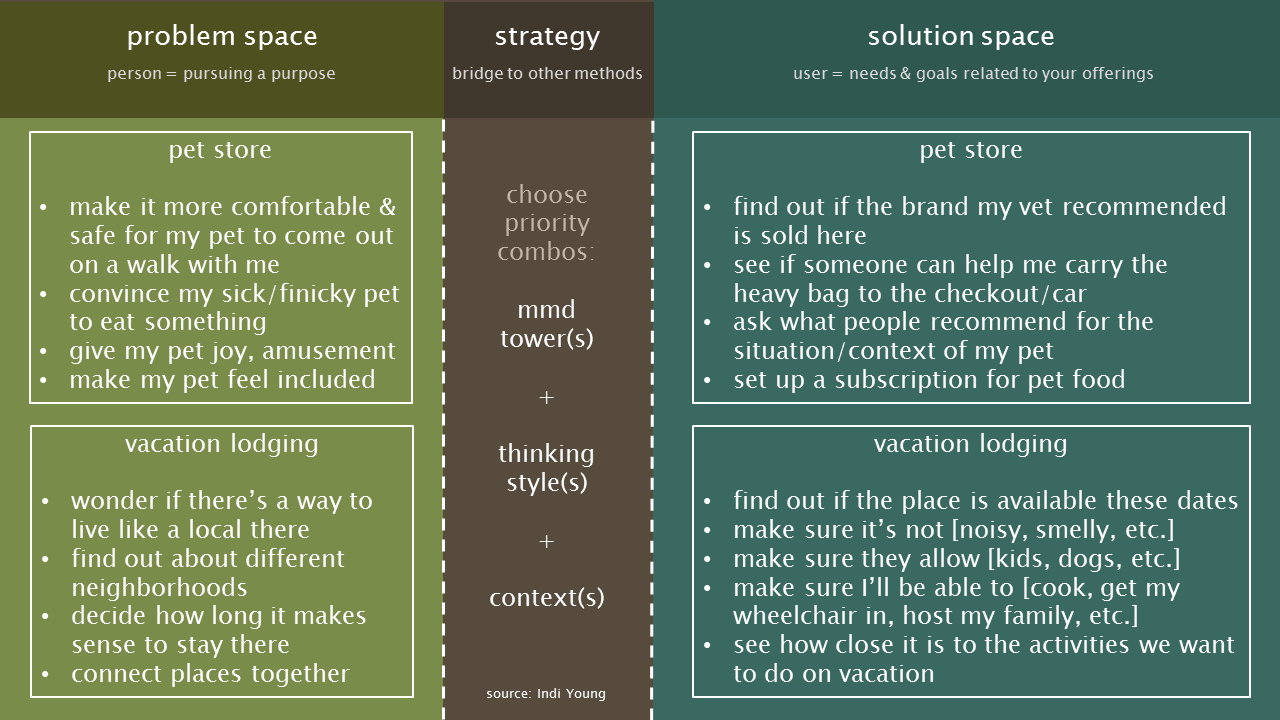

A: Yep!! Here’s a good diagram to get you started. I speak to this in my course on using mental model diagrams as opportunity maps. Basically this is a deeper method that provides a more solid foundation for JTBD … the diagram shows how the concepts map easily back and forth. I do talk about it in some podcast appearances that are listed on my site.

Q: I remember attending a talk you gave referencing the image below. A challenge I have is to group various user types based on thinking-style. Personae have been used by Agile coaches. I am having a hard time to convince folks to frame users based on thinking style instead of job titles. any thoughts? – Chika A.

A: You can totally use the word persona to mean thinking style, if that works better for your context. Or you can use “archetype.” There is a problem with any archetype that uses demographics to describe the group: invites subconscious bias. (Unless those demographics are related to a context of discrimination, physiology, and a couple of others.) When you explain to someone how demographics cause assumption, they don’t need to be convinced further. Here are two helpful articles: Challenging the Make-Believe in Personas and Demographic Assumptions.

AMA with Indi Young, author of Practical Empathy and Mental Models

Posted on

Join us on Slack for an “Ask Me Anything” with Indi Young, author of Practical Empathy and Mental Models. She’ll be answering your questions live on Tuesday, December 1 from 2-2:45pm EST in our #rm-chat channel. Join our Slack here.

Peak empathy? No, Practical Empathy!

Posted on

Given that Indi Young and I first began discussing her new book idea many, many years ago, Practical Empathy: For Collaboration and Creativity in Your Work was a marathon in the making. Even the last mile proved to be full of unexpected (and unpleasant) challenges.

Given that Indi Young and I first began discussing her new book idea many, many years ago, Practical Empathy: For Collaboration and Creativity in Your Work was a marathon in the making. Even the last mile proved to be full of unexpected (and unpleasant) challenges.So I’m thrilled (and relieved) that, as of today, Practical Empathy is finally available! And not just in paperback; like all of our books, it’s also available in DRM-free PDF, MOBI, and ePUB formats. Learn more at the book’s site, where you can sample the table of contents, illustrations, FAQ, and read testimonials like this one from Karen McGrane:

Your product design should be informed by a deep understanding of user goals. In Practical Empathy, Indi outlines a way of working that goes beyond data-driven research methods to deliver genuine empathy for the people who use the things we make.

By the way, I know what you’re thinking: everyone’s talking about “empathy” lately. Are we at the point of having reached peak empathy? The answer really depends on what we mean by the word.

And Indi’s take on empathy is quite different than what you might assume:

This book is not about the kind of empathy where you feel the same emotions as another person. It’s about understanding how another person thinks—what’s going on inside her head and heart. And most importantly, it’s about acknowledging her reasoning and emotions as valid, even if they differ from your own understanding. This acknowledgment has all sorts of practical applications, especially in your work. This book explores using empathy in your work, both in the way you make things and the way you interact with people.

Yes, we all could stand to be more empathetic in the ways we feel about others. But Indi’s book focuses on cognitive empathy, which offers a huge and hugely practical payoff to anyone involved in just about any aspect of design. We hope you’ll enjoy the payoff from reading from Practical Empathy.

Unanticipated delays on shipping Practical Empathy

Posted on

Sorry to bear bad news, but Practical Empathy—which was to ship today—is apparently the victim of a printing SNAFU. Here’s the situation, and what we’re doing to address it.

Becoming Person-Focused

Posted on

(08-Dec-2014 Author’s note: The book is finally at the press! It will be out within weeks. In the interim, I decided I’ve been silent too long on this blog, so here’s an empathy story to carry you along.)

Walking in someone else’s shoes gives you understanding about where this other person comes from—what experiences he’s had that shape the way he thinks and acts. Understanding several other people gives you insight into the vast spectrum of perspectives that exist out there. This kind of understanding is ambiguously referred to as “empathy.” It works in understanding your customers, and it works in collaborating with your peers at work.

Here’s an example story, with components stitched together from many realities.

Savi is the director of User Experience at a large insurance corporation. This is a new role at the organization, and she was hired 10 months ago to build and lead a new internal team providing customer research and strategy. How Savi makes her role into a success is based on carefully understanding the thinking of the people around her. For her internal work, she adopts the same philosophy she uses to understand customers. She stops focusing on her own goals and endeavors so that she can grasp her co-workers’ goals. This is how empathy can be harnessed: deliberate understanding of all the kinds of people involved in your work: customers and co-workers. This kind of empathy is about making the space for new insights to emerge. The insights might be tiny things you already knew, but didn’t pay attention to, or they might be significant revelations. These insights allow you to re-frame things so that you can support people better.

Savi & Her UX Team at BigInsuranceCompany

Pretend this is Savi and her team. (In reality it is a group of students from General Assembly SF, summer 2014. Some of them might become a Savi one day.

“As an organization, we’re going to become more customer-centric.” Saying that is one thing. Making it happen is quite another, as Savi knows oh-so-well. So far she feels like she hasn’t made any difference.

In the first few weeks after coming on-board, Savi defined what she wants her group to provide to the organization: not only review, testing, and tweaking how customers are supported with current products, but also more strategic stuff. She wants to help the company understand what people are up against in their lives, and what their thinking is right before they turn to insurance. She knows there’s more to understand, and better ways to support customers. It’s just that, right now, upper management isn’t listening to her. Even though they agree about the customer-centric goal, and they hired her and gave her a budget, they are reluctant to give her a seat at the table. Savi has tried to show them how her group will be able to make a difference. She has invited senior management to presentations about her goals, but if they even attend, they just nod and apologize for having to rush off to their next meeting. She asked her boss for time to make her presentation at two of the quarterly business meetings, but both her requests got denied. The message from the highest decision-makers seems to be, “What you aim to do sounds good. Go do it.”

The problem is, without explicit instructions to do so from upper management, none of the other divisions in the organization think to include Savi in their work. So she attends their meetings and offers recommendations. She asks what areas people need to know more information about. All she has heard in return is empty praise of her goals, but no concrete requests for knowledge. Her recommendations are met with distrust, because she is new to the insurance field. Savi figures if she can get some kind of change made that results in measurable success, then the others will start reaching out to her. It’s just getting that first success to happen which is hard.

Also, there is the problem of hiring people to work on her team. Within eight weeks of starting her new role at the insurance company, Savi had interviewed a few candidates and hired one. Luckily the company headquarters office is based in a popular area, so finding a few candidates wasn’t as hard as it could have been. Just the same, Savi recently learned that competition for the good employees is strong. The person she hired resigned last week, citing better opportunities to actually engage with customers and get some research done at another organization. So now, Savi has to start the search for candidates again. It’s just one more setback contributing to her sense that she hasn’t accomplished anything.

Savi knows she needs to make the higher-ups pay more attention to customer strategy. But recently she read some articles and watched a few presentations which made her reassess her approach. The theme is about understanding other people at a deeper level. Usually the focus is on customers, but Savi is thinking she will turn her energy toward understanding the people around her at the insurance company. If she understands what’s driving upper management, then perhaps she can support them better without clamoring for attention. If she understands where the distrust comes from in the other teams she’s supposed to be collaborating with, then maybe she can provide them something that speaks to it. Perhaps her own words “make them pay more attention” need to change to “pay more attention to them, myself.”

So, Savi embarks upon a fresh path, making room in her daily schedule to go listen to someone for 30 minutes or so. If she’s going to be the person who coordinates the focus on customers, then she had better be in touch with all the other people involved. She had better understand what thinking is going on and how decisions have been made. She had better understand the people she hopes to coordinate. She listens to her boss, and to his boss and more of upper management. She listens to the leaders of various groups throughout the company, and some of the team members. Sure, the logistics of a 30-minute appointment with so many different people fails a lot of the time, but the sessions she does manage schedule turn out to be exactly the rich source she expected. She walks into each meeting simply with the intent of understanding what’s been on this other person’s mind recently. The conversation goes where it will, as the person grows accustomed to Savi and begins to describe the way he weighed a decision, or how he realized when he didn’t know enough about something, and how he filled in the blanks. She goes into each meeting without a personal agenda. She doesn’t try to explain anything or persuade—she simply listens to each person’s concerns and digs into the details to understand more clearly.

Out of five days a week, Savi gets to listen to about three people, on average. After a month of this, she begins to see patterns in the ways some people think, and differences. One pattern is that the people who have been with the company a long time really understand the products, and the legal limitations of what the company will do for a customer. They are concerned that the customer wants to bend rules and make exceptions when filing a claim. So this is the first topic she pursues in her research—while also keeping up the 30-minutes-a-day scheduling. Those meetings she will never give up, since they are such a strong way to keep on top of what the people around her are thinking.

Savi’s research gathers all the exceptions the company has made for a claim in the past, as well as all the exceptions that customers asked for (exceptions which were documented—many were not) but did not receive. She listens to a few customers tell her their reasoning process behind asking for an exception in their particular case. She synthesizes this data and finds patterns, which she then shares with people in a series of small working sessions. She doesn’t come to these sessions recommending ideas—instead, she asks people what they see in the data, themselves. She asks if anyone has different interpretations. She asks if the ways things work now is sufficient for typical customers, or sufficient for particular sub-types. And always, invariably, someone in the room makes a suggestion. The suggestion may be a big idea or a small idea. Most likely it will get changed as people discuss it and poke holes in it. But Savi is pleased even if the idea dies entirely. The groups she is working with are willing to look at life from the context of a customer—they’re able to shift their perspective enough to squeeze past the seemingly unsurmountable mind block of the legal restrictions. This way of building trust and collaborating in a way more supportive to people’s concerns is working. Rather than the narrower domain of “customer-centric,” Savi has broadened it to a “person-centered” approach which includes decision-makers and team members at the company, as well as customers.

Savi’s success depends upon ongoing sessions with individuals, and upon bringing findings to small groups for discussion. It’s a core part of her role. Now that people at the organization feel her support, they want more and more information from her. They know she’s not going to force ideas upon them; they can trust her. They know she listens and prioritizes across the topics she hears. They reach out to her when they find a hole in their understanding about customers—and they’re less reluctant to acknowledge that the hole exists. No one is to blame, and Savi always comes up with knowledge to help them make better decisions and move forward. No one apologizes about having to leave to get to another meeting, because these are the meetings that feel the most productive. People participate. In fact, it has gotten to the point where Savi has to regretfully put some requests on a waiting list; she has hired another person to help gather the knowledge, and now she realizes she’s going to need to hire a second person to help out.

What Makes Savi’s Story Different

The story demonstrates a shift in attitude away from fighting for internal attention and toward including people you work with in the same philosophy that you use to understand customers. This more outward-focused attitude is something you might call the empathetic mindset. It’s a mindset that you can practice anywhere, taking short little forays into this style of finding out what the other person is thinking.

Why Get a Book Signed?

Posted on

Why Get a Book Signed?

When I was a new author, one of the more disorienting experiences was the first time someone came up to me with their copy of my book and asked me to sign it. I was happy to do it. I was also bemused–not that I wasn’t familiar with the behavior, but why would a person ask me to sign their copy of my book? It seemed to be a habitual thing: people who have a hardcopy of the book with them when they encounter the author ask for a signature. I was curious about this decision. What was going on in that person’s mind? My curiosity grew when another fellow said sadly, “Oh. I bought an electronic copy. I guess I can’t have your signature.” (This point is probably part of the ongoing discussion out there about digital rights and value.)

Recently, I had a chance to find out why. I was at a presentation by Malcolm Gladwell, for his David and Goliath book tour. Everyone who bought a ticket was given a copy of the book. The organizers, a local book store called The Book Passage, promised we could queue up after the talk and get our books signed. (All 400 of us!) The organizer even made a quip about how the value of a signed copy is better than an investment in the stock market.

Malcolm Gladwell presenting, San Rafael, CA – 09-Oct-2013 So, after Malcolm told an illustrative story about a domineering rich lady, Alva Vanderbuilt, becoming a leader for the womens’ right-to-vote movement, I had a whole theater-full of people to ask. “Why are you getting your copy of the book signed?”

(Note: The other related question is “Why get a copy of a signed book,” but that didn’t apply to this scenario, if you interpret that question to mean, “Why buy a signed copy?”)

Here are some of the answers I heard. I tried to ask people of all ages and genders and physical appearance. I even asked people who looked like the didn’t especially want to talk to me. I probably asked 12 people. Not a huge sample size, true. This subject deserves more in-depth attention. But here’s some of what I remember:

- “I admire his ideas.”

- “I want to thank him for writing about all the ideas he writes about.”

- “I am a fan of his.”

- “My father is a fan of his. So I’m getting my copy signed, too.”

- “I want to say hello to him.”

- “It’s something different. I only own two signed books.”

- “I don’t own a copy of the book. I’m a student–a junior political science major–so they gave me a ticket but not a book. I can’t afford to buy the book. I brought my copy of Outliers for him to sign because I admire his work.” (I did try to offer this person my copy. Heh.)

- “I’m building a nice collection of signed books by authors I admire.” (I should have asked why!)

- “When I loan a book to my friends, they’re more likely to actually read it if it’s signed.” (Assumption: My friends say that authors who are asked to sign books must be good.)

- “I want to give him a copy of the book I wrote.” (Assumption: I admire him and I think he’ll see that admiration in my work. I should have asked him about his book!)

- “I’m not getting my copy signed. I’m in line because my husband wants to meet him.”

- “I don’t know–everyone is doing it, so I want to, too.”

- “Why? Are you trying to decide?”

None of the people directly mentioned adding monetary value to their physical copy of the book. One of the comments obliquely reference it, as in “collection,” but that could be a collection for personal reasons. There might have been people in that theater who would have told me about the monetary value a signature adds to the book, but I didn’t happen to talk to them. So. This is not exhaustive research. It’s simply practice at being curious about what’s going on in other people’s minds.

I was talking with my companion, Rainey Straus, and she told me she’s gotten books signed in the past because:

- “My friend wrote the book, so it was in support of her.”

- “My boyfriend got a copy of a book signed by an author I liked and gave it to me as a gift.”

I tried to briefly get inside people’s minds. I went back and forth with them for a minute or two. I didn’t have enough time to really ask for details, though, so any sort of translation I do is precarious. And this list is certainly not complete.

Reasons Why People Get Their Book Signed By the Author

- mark solidarity with the ideas the author writes about

- express gratitude to the author directly

- make a personal connection to the author

- mark the ideas in this book as important, from all the books I own

- celebrate a person I have a relationship with, by giving a signed book (more so than an unsigned copy)

- encourage a friend’s (or family member’s) creativity

- go along with what everyone else is doing

And surprisingly, as I was wandering up and down the line of people, I found myself in line. So I went along, got in front of the table, and had my book signed by Malcolm Gladwell. I asked him how his hand was holding up. “It’s getting there,” was that I remember him saying, implying that he was starting to feel some fatigue. I don’t think I could equal his endurance.

Thank you, Malcolm!

Signed title page of Malcolm Gladwell’s book: David and Goliath. Welcome!

Posted on

It has been so much fun, so far, writing about empathy. So many more individuals and organizations than I imagined labor to spread the concept. They all recognize it as a tool for achieving, if not harmony, at least a broader perspective. Empathy has become the battle cry (irony intended) of those tired of battle, in areas from international politics to school bullying to product strategy. It’s fascinating how much excitement has been building up about it, in all sorts of different applications.

What’s also fascinating is that it’s hard to pin down. There are almost as many different meanings for empathy as there are applications of it. Everyone earnestly tries to explain what they mean and how it helps, but there are few techniques and guidelines not hidden behind a paywall. So my book will lay out the practices you can incorporate into your life and work–achievable little tidbits that you can work on over the months and years of your career. For instance, I will teach you how to elevate the intelligence and expertise of the person you’re trying to understand above your own level. You are not the expert in the way their reasoning flows, so I’ll teach you how to quell your own instincts and absorb their narrative. That’s one little tidbit.

And while this book is aimed at people working on a service or product, empathy really ends up affecting your personal philosophy, as well. As you get better and better at it, you’ll find it spilling over into all sorts of arenas. And that has been the thing I’ve found most gratifying in my own life. Being an introvert, I feel like I’m woefully behind in my skills at understanding other people. The practice of empathy in my work has started to improve how I react to others. I’m finally able to defuse some of the arguments with my significant other, hallelujah!

It will be my great pleasure to share this book of concrete, everyday practices toward empathy.