-

20 User Research Questions Answered by Laura Klein & Steve Krug

Posted on

I recently got to interview Steve Krug, author of Don’t Make Me Think and Rocket Surgery Made Easy, as the lunchtime entertainment during the User Research for Everyone conference. I always enjoy talking with Steve, which meant that we spent most of our time chatting and then ran out of time to answer all the questions submitted by the audience.

Sorry! To make up for that, Steve and I have answered some of those questions here. A few have been edited slightly for clarity and brevity.

Question: Our company ran an unmoderated usability test where we tasked users to try to find a bit of information via search. 95% of people didn’t type anything in the search box before clicking done. They just wanted the incentive. I looked through all the records of their sessions to see who seemed to put in a good faith effort and who didn’t. But that took a lot of time and effort. How can we get around this?

Laura: The first thing I thought when I read this question was, “You should be watching all the sessions.” That’s the value of usability testing–seeing people use your product. If you’re just making people use the product and then giving them a survey at the end, you won’t get very good feedback.

Most companies that help you do this sort of testing let you rate your participants. If you feel like the participants really aren’t fulfilling their end of the bargain and are just clicking through at random for the incentives, give them a 1-star rating and ask for your money back. Companies aren’t interested in recruiting bad testers for their panels.

In your case, I want to know why they didn’t search. Was it because they couldn’t find the search box? Or because they could find what they were looking for without searching? Did they understand the task? You’ll only understand their motivations for not completing the task if you actually watch the sessions you’re paying to have people run.

Steve: Well said, all of it! You’ll only understand their motivations if you watch what they do (and listen to them thinking aloud, of course). This is fundamental. It’s the reason why qualitative methods give you insight into why things happen, as opposed to quantitative methods that only tell you what happened.

Question: Roughly what % of companies do you believe actually conduct usability testing?

Laura: I have no idea, but it’s far too low. In my experience, it varies wildly based on industry. Even what people count as usability testing varies. For example, a lot of consumer packaged goods companies do lots of customer testing, but they’re not run in the same way that a software company might run it. A lot of companies say they usability test, but what they really mean is that they’ve run a few tests in the past once in awhile. Or they talked to that user only one time.

I’m curious why it matters to you? The important thing is that the percentage of those who test keeps going up!

Steve: 21.5% (in keeping with the notion that 64.4% of all statistics are made up on the spot). Laura’s right: whatever the actual number is, it’s far too low. It’s why I spend a lot of my time showing people how they can reduce the amount of time and effort required, and make sure they’re really doing a usability test (i.e., watching people try to use the “product” while listening to them think aloud). The good news is that even though the percentage is still way too low, it’s much higher than it was a few years ago. And it continues to grow.

Question: What’s the simplest user research we can do?

Laura: As Steve said during the session, and in greater detail in the interview I did with him for my new book Build Better Products (shameless plug–you can buy it now), the simplest form of user research to do is usability testing on competitive products. It’s a fantastic and useful method for getting feedback on products.

Cindy Alvarez also mentioned using this method in her talk. She pointed out that it’s a great way to get people excited about usability testing and start to learn the techniques without threatening to make anybody inside the organization look bad.

Steve: And there are other research methods that are reasonably simple: like doing some user interviews. Interviews can be particularly simple if you do them remotely since you don’t even need to physically “get out of the building.” (Sidenote: the need to at least metaphorically get out of the building is one of the many terrific things the Lean UX movement—and Laura’s books, etc.—have introduced a lot of people to.) Interviews produce whole different kinds of insights than usability tests, but they both can be very rich.

Question: I am currently the UX strategist for a global law firm where I am tasked with designing tools for attorneys. My users are within reach, which is a great thing. But lawyers are pressured to fill all working hours during a working day with billable hours. I can’t figure out how to reach these users given their tight time constraints. Any ideas?

Laura: The easiest thing you can do is to compensate them for their time. Whenever you’re recruiting professionals, it’s important to recognize that their time is valuable and offer them something. It might not be money. It might be a donation to charity or a bottle of wine. But it has to be something that they think is valuable.

Also, try getting smaller chunks of their time. Asking for an hour is harder than asking them for a 15 minute call or screenshare. Offer times at lunch and before or after work. Try to do it remotely or go to them so that you’re not asking as much. Look for other types of lawyers: some in-house counsel jobs have regular salaries, and those lawyers aren’t as likely to have to account for every second. If you’re just doing usability testing, you don’t necessarily need the exact lawyers that you work with to help. You might be able to use other lawyers to see if they understand the interface. That will give you a lot larger pool of possible participants.

Steve: All great. And what about working with management to get the time they spend testing categorized in some way that recognizes its value?

Apart from this corner case (billable hours), testing internal tools (or intranets) is often easy, because you know exactly where to find a large pool of actual users who have a pretty good incentive to help. Often the best subset is new hires, because while they’re actual users with domain knowledge, they’re not yet familiar with the internal tools.

Question: How important is it to do usability testing on a user’s own computer/device/environment? Compared to bringing them into an office?

Laura: It always depends on what you want to learn. When possible, I prefer remote to forcing people to come into your office, since it means you’re not being geographically biased in your participant sample. On the other hand, seeing their environment in person can give you a lot of insight into their context of use.

Steve: And of course remote has so many other advantages, like no travel time and expanding the recruiting pool from “people who live or work near you” to “almost everybody.”

Laura: I’d say that contextual learning (home visits, etc.) is a lot more important for user research as opposed to usability testing. If you’re just interested in seeing if people can perform certain tasks given a particular interface, I’d go with remote testing. If you’re really digging into the way people work or perform tasks in their natural environment, consider whether you need to be more immersed in that environment.

Steve: Only one caveat: if you’re bringing them in, you need to make some effort to ensure that your computer setup isn’t going to get in their way. The most common case is sitting people down at a laptop with a touchpad when they’re only comfortable with a mouse. The solution, of course, is to have both available. You may also run into issues with Mac vs. PC users, but only if the test tasks are going to involve interacting directly with the operating system. If you’re testing something in a Web browser for instance, it probably won’t matter.

Question: What user research would you recommend for non-homogeneous target groups? From users with basic knowledge to super-professionals?

Laura: I’d recommend focusing on a specific subset of people and making things better for that identifiable group. Often, when you try to make improvements “for everybody” you end up making things better for nobody. Understand who you think your changes/new features/improvements are for and what behavior you expect to change, and then usability test on that subset of your users.

Steve: And I’d recommend beginning by focusing on the people who live on the “basic knowledge” end of the scale. If they find it usable, the people with more knowledge/experience will probably be able to figure it out. Remember, you’re not dumbing things down: you’re making things clear. Everyone appreciates clarity—even power users.

Laura: If you are making a global product change, make sure you understand the different segments of your users and recruit participants from each segment. You’ll most likely want to run a few more sessions than you would otherwise, to make sure you don’t have just one of any group.

Question: What are some ways you’ve successfully distributed findings from usability testing—particularly when some of the most interesting findings aren’t relevant to the topic you were researching?

Laura: It depends on who the user is of the findings. I wrote a post on deliverables that might be helpful. Whenever you create a deliverable of any sort, treat the recipient of the deliverable as a user of a product. Present the findings in an appropriate way for that person.

In general, the best way to make people familiar with the findings is to invite them to help with analysis, but I understand that that’s not always realistic.

Question: We have a really distributed team. What are some good strategies for getting everyone to watch people use our software when it means asking everyone to watch two hours of video?

Laura: Does everybody need to watch all two hours of video, or could you cut a highlights reel? I’ve had better luck going through the videos and grouping responses or tasks together to make it easier for people to consume.

Another option is to schedule an online analysis session with stakeholders where you use a digital whiteboard like Murally to share insights. You can require stakeholders to watch the research ahead of time. Just givethem a deadline and a reason to encourage them to watch the videos.

Steve: If you don’t have the time to create a highlights reel, you can simply crop out the time-wasting parts. And then give the viewers a tool that lets them watch what’s left at faster-than-normal speed. I never watch a usability test video at less than 1.4x normal.

Question: If you only have three slots and test three different pieces of functionality, is there enough enough feedback to recommend changes?

Laura: It depends, unfortunately. There have been usability tests where I knew there were enormous problems after half a session. I still ran a few more sessions after that to confirm, but it was very clear. In general, you run the sessions you need to run to start to see patterns.

Question: For an overall junior team, is it fine to start out doing internal usability testing–despite its limitations due to things like bias–to get up to speed and gain confidence?

Laura: Sure. In fact, I really like the suggestion from one of the speakers that you run a pilot on a member of your own team (like the designer or PM) at the beginning of all usability testing, regardless of how senior your moderators are.

Just keep in mind that what you’re learning from internal people will likely be extremely biased. Use it as a training tool, but I wouldn’t take the results nearly as seriously as I would results from real or potential users.

Also, ask yourself whom you’re protecting by keeping your junior folks away from users. If you feel like they’re going to damage customer relationships, try getting them some one-on-one coaching or training. Then have them practice on friendly customers. If you’re worried that they’ll get bad results, they’re no more likely to get bad results from external participants than they are from internal ones.

Steve: Yes, pilot tests. It’s too bad we didn’t get to talk about pilot tests since they’re absolutely essential. If you don’t do a quick pilot test before you bring your participants in, you’re not doing it right.

Question: How strongly do you feel about having one person per session? I’m part of a team developing an internal tool for a large company. I’ve got access to users in-person (our employees) twice a month and my boss thinks it’s better to test or interview two or three people at a time.

Laura: I have very strong feelings about this. As I mentioned during the Q&A session, I’d want to know why my boss wanted to interview two or three people at a time. Is it for convenience? Or because they think you’ll get better results? Hopefully you can talk them out of it, because neither scenario is true. You’ll end up getting a lot of echoing and learn more about power dynamics in your company by interviewing multiple people at once.

If it’s a tool that people will use jointly, it can make a lot of sense to structure sessions in a way that helps you understand how that will happen.

Question: The big benefit of the model that you’re describing for usability testing comes from synchronous participation (and discussion afterwards.) How do you apply this model in globally distributed teams?

Laura: Well, you can get huge benefits from usability testing when it’s just the researcher/designer/PM doing the research, finding problems, and fixing them. You don’t technically need everybody involved in that process.

The more people you have involved, the easier it will be to get the changes made. Especially if you’re in an environment where people tend to want to ship it, forget it, and move on to the next thing. Get creative—create things like video highlight rolls that you can share widely or snippets of information that are easy for people to digest.

Steve: It’s true: you don’t technically need everyone involved in the debrief process. But I think it’s worth bending over backwards to get as many people involved as you can (hence my “make it a spectator sport” maxim). Having more people involved does increase your chances of having durable buy-in and getting the changes made. But you’re also filtering the problem through more minds with different perspectives and valuable bits of information about where the bodies are buried. I also think that the process of observing and debriefing makes people better at their jobs, something I think of as “informing their design intelligence.”

For globally distributed teams, maybe some people watch the recorded sessions at a more convenient hour, then come together the next day for a full-group debriefing session.

Question: Are your users who you think they are?

Laura: Sometimes?

Question: Laura, what are the three most common questions you get about research?

Laura:

- How do I recruit people?

- How do I answer this particular question?

- How do I convince people that research is valuable?

Not necessarily in that order and not necessarily in those exact words. I was happy to see that those were big themes in our research before the conference, since now I can point people to a bunch of experts answering those questions.

Question: In a publishing environment, the editor is considered the authority on editorial content. What’s the best way to disavow editors of the notion that their editorial power also carries into UX of that editorial content?

Laura: Ha! You could literally replace “editors” with any other professional who is an expert in their thing – lawyers, doctors, scientists, etc.

Be open to what they’re recommending. Remember, they do have more domain expertise than you do. Understand why they want what they want. It may be that there’s a third solution that takes their concerns into account better than what you’re proposing.

And never underestimate the power of testing—either usability or a/b. If you’re advocating for one solution and your stakeholder is advocating for another, you’re going to have to devise a test that will definitively show which one of you is correct. This is literally what a/b testing is great for if you have enough users. If you don’t, then having a neutral party run usability tests on two different variations of a prototype can also be very eye opening.

Question: What do you think about pinging other UX professionals for usability and testing of prototypes other UX pro’s are working on?

Laura: I’m not a fan of asking other UX folks to do usability testing of prototypes, unless, it’s a product for other designers. You’re typically much better off testing on a few of your real users or potential users rather than asking someone who does this for a living.

Remember, UX designers aren’t magic. We don’t automatically know what problems real people will have and instinctively know how to fix these problems. If we did, we wouldn’t need to usability test! UX designers have the curse of knowledge. We don’t look at a product the same way other people look at it. If it’s a product for a specific group of people, designers can lack the domain expertise to give you decent feedback about what might be confusing.

That said, after you’ve run usability tests with your target market, other UX designers can often be very helpful in suggesting other ways to approach the problems you’ve identified. They may have seen other users have similar problems and have ideas about what worked to fix those problems.

But you still have to test with users.

Question: What’s the approach for testing content heavy, inspirational websites? Think TED.com.

Laura: Same approach for everything else–figure out what you’re actually testing and then come up with something that will help you learn what you need to know. Are you trying to test whether the website is usable? Inspirational? Understandable? Useful? Those are all very different types of experiments that you want to run.

The type of product is not what determines how you test. You test based on what you want to learn.

Question: I’m wondering if we’re too biased to effectively help others.

Laura: Depends on what you mean by “we” and “help.” Humans are extremely biased. It’s kinda our thing. There are ways to acknowledge and counter that bias to some degree, although I don’t think that most of us will ever even come close to getting rid of it entirely.

In general, the more time you spend listening to others and the less time you spend thinking about you and how you would do things, the less biased you’ll be.

Question: I often hear “I would have designed it differently.”

Laura: Yeah. We all do!

The best follow up is, “I see. Why would you do it that way? What problem would that solve for you?”

Frankly, I don’t care if they want a big red button to push that says “push me” on it. I want to know why they think that button will help them. Think of solution requests as a jumping off point to understand what their problem is.

Steve: We in the usability racket like to say “users aren’t designers.” And the truth is, they aren’t. Every once in awhile (once in a great while, actually), a test participant will make a terrific suggestion. You know when this has happened, because everyone in the observation room slaps their forehead simultaneously and says “Why didn’t we think of that?” But 98% of the time, design suggestions from participants aren’t great. I always recommend listening politely while they make the suggestion so they know you’re paying attention to them. Then at the end, after they’re finished with the tasks and you’ve moved on to open-ended probing, you can remind them of their idea and ask them to explain how it would work. In my experience, they’ll almost always end up by saying some variant of “But actually, I probably wouldn’t use [the new version] because [reason]. It’s better the way it is.”

Question: Is there a point of diminishing returns with too little user research? That is, is there a fear that a little learning can be a dangerous thing, leading to a false sense of UX security?

Laura: Sure.Talking to one person and then immediately diving in and solving all of their problems can certainly cause problems. If that person is an outlier. You don’t necessarily want to design your product around exactly one user. On the other hand, you can also spend an awful lot of time trying to “prove” yourself right.

I wrote a blog post on Predictive Personas that is probably applicable here. You can use this for usability testing just as easily as for predicting who will use your product. The idea is to run some sessions, try to spot patterns, predict what you’re going to see next, and then see if your predictions hold. Once you’re making predictions accurately, you’ll have a good idea of the recurring problems in your product and can more confidently start fixing them.

Laura Klein is a Lean UX and Research expert in Silicon Valley who teaches companies how to get to know their users and build products people will love. She’s a Rosenfeld Media expert and author of Build Better Products, and UX for Lean Startups (O’Reilly). Follow her on Twitter or subscribe to her blog and podcast at Users Know.

Steve Krug is best known as the author of Don’t Make Me Think: A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability and Rocket Surgery Made Easy: The Do-It-Yourself Guide to Finding and Fixing Usability Problems. Steve spends most of his time teaching usability workshops and consulting. Follow him on Twitter.

Buy on-demand access to the User Research For Everyone program.

Analyzing the Research Behind User Research

Posted on

Without user research, you risk designing ideas that users don’t want. Let’s be honest: many organizations don’t know how to successfully do user research. Too often research gets treated like an item to knock off a checklist just before products get shipped out. Or it’s skipped altogether because “there’s just no time.” Even with good intentions, the lack of in-house expertise can stymie us. We end up conducting focus groups. Or approaching strangers in Starbucks–asking them how much they’d pay for our new product.

We researchers, designers, and product managers want to understand what makes great products that customers will buy, use and recommend to friends. But without research, this can feel impossible.

This is such a pervasive pain point that Rosenfeld Media has made user research the topic of our next virtual conference: User Research for Everyone. The goal: to help you figure out how to build a team that is excited about research and empower it with the tools to make research useful.

Before designing the program, I helped Lou conduct some research (obviously). Research on user research–yep, pretty meta. Almost 200 of you weighed in and told us the areas you struggle with most, and who you most want to learn from. The responses clustered nicely into six prevailing topics:

“How do I convince people research is important?”

Convincing leaders and teams to see the value of user research is the top question you submitted. We agree. Research works when everybody is on board, but making people care is challenging. Especially if you work in a large organization and need to persuade multiple stakeholders with competing agendas.

“How do I turn this research into better products?”

We’re often told to get out of the building and talk to users, but that can create a five-story pile of research. Distilling and choosing the right insights to inform product decisions is time consuming and daunting.

“How do I make sure everybody understands the research?”

Research can only inform design decisions if everybody on the team understands (and agrees on) the results. How many of you have created a 30-page deck that nobody ever looks at? Many of you said you’re eager to discover more compelling ways to share and evangelize research that people want to absorb and use.

“How can we do this faster and cheaper?”

Most of you face real budget or time constraints–making research seem like a pipe dream. But it doesn’t have to stop us from learning from users. A lot of respondents want techniques for doing remote research to cut costs, or to shorten the timeframe to work better in an agile environment. Luckily, there are a lot of tools and tactics available these days to help make good research achievable and affordable for any budget.

“How do I pick which research to do?”

Many of you have difficulty picking the right methodology to answer your questions. Even experienced researchers can struggle to understand how to incorporate quantitative data into the research process. Many of you request better frameworks for deciding which research to do when.

“How do I get more participants?”

Even when you’ve got a good understanding of who your users are, there’s still the challenge of getting them to talk to you. This can be especially tough when you’re in the early days of a product development and don’t yet have real users. In established companies, you need to coax sales or marketing people to let you talk to customers. There are better ways to reach the right users without resorting to begging or bribery.

Getting to Answers

Join us on October 11, where we’ll tackle these important questions with the experts you requested most: Abby Covert, Steve Krug, Erika Hall, Nate Bolt, Leah Buley, Cindy Alvarez, Julie Stanford and me (as moderator). The program includes Q&A opportunities with every expert–so you can ask your most top-of-mind questions.

Buy a ticket for yourself–or your team and build the user research toolkit you’ve wanted. Your ticket also gives you unlimited access to downloads and replays of the full program in case you can’t make it.

Thanks to all of you who participated in the survey. Hope to see you there! And hit us up with any questions and thoughts below.

Laura Klein is a Lean UX and Research expert in Silicon Valley who teaches companies how to get to know their users and build products people will love. She’s a Rosenfeld Media expert and author of UX for Lean Startups (O’Reilly). Her newest book, Build Better Products, comes out in late 2016. Follow her on Twitter or subscribe to her blog and podcast at Users Know.

Whose Job Is User Research? An Interview with Celia Hodent

Posted on

Celia Hodent, Director of User Experience, Epic Games This is part 4 in the series Whose Job is User Research.

In this series I’ve been gathering perspectives from experts who develop different types of products. This time I spoke with Celia Hodent, Director of User Experience at Epic Games, a company known for cutting-edge technology and design in the video game industry. Celia also holds a PhD in Psychology so she has tremendous insight into how to use user research to improve the gaming experience.

Who Owns the Research?

It turns out that building games isn’t that different from building anything else. The user experience is a concern for everybody on the Epic Games development team. Research helps them understand more about their design. “The goal of UX research is to test whether design intentions are the ones actually experienced by the target audience,” Celia said. Research also identifies all usability issues that need to be resolved.

Like other great UX designers I’ve spoken with, she says that research should not be separated out from the design process. Research informs and supports the whole design process–which means that everybody needs to be involved.

“Owning the research is not just about conducting the research,” Celia says. “It guides the product team so that they ask the right questions, pose hypotheses, and make sense of the research results in terms of actionable items.”

Who Does the Research?

At Epic Games, Celia relies on expert researchers to conduct the research in the best possible way.

“When it comes to research methodology though,” Celia says, “the people handling research should be the ones who know how to design and carry it out.” Celia outlines four key steps:

- Defining the right experimental protocol to test the product team’s questions

- Running the research

- Analyzing data

- Communicating the results to the entire development team, as well as with other support teams such as Analytics or Customer Service to cross-check results against their data

Professional researchers, and sometimes outside researchers, can also help to reduce bias. “It is very hard to stay neutral when conducting research, even more so when you are part of the development team,” Celia says. Therefore, an expert researcher is more likely to get to the bottom of the research questions without preconceptions or confirmation bias.

When Do You Call in Researchers?

A common mistake Celia has seen companies make is reducing research to usability testing. Too often, product teams forget to involve researchers until after design is complete. By then, all they can do is find bugs.

Instead, Celia recommends bringing researchers into the entire game design process. “Whenever design iterations are conducted,” she says, “which happens as early as pre-production, the designers should pair up with a researcher to run quick-and-dirty tests.” You can use paper prototypes and interactive prototypes–before engineers start implementing a feature. It saves a great deal of time. You’ll find the high level UX issues early—they are cheaper and simpler to fix before you’ve implemented anything.

What To Do If You Don’t Have Researchers?

The truth is that many teams simply don’t have people familiar with good user research techniques. Celia has six tips to running research yourself:

- Prepare your test well: be clear on what your design questions are and design the test to obtain relevant answers.

- Tailor your protocol to your research questions and what you’re testing. For example, to test how gamers understand your heads up display (HUD), you can simply take them through a survey showing screenshots. But, if you’re testing how a new feature is introduced to a player, you’d use a “think aloud” protocol. Ask the participant to play through the game while explaining what their thought process. This shows you if they understand the interface as they go.

- Test with people who don’t know you or your feature. People who know you will be more motivated to make an effort to figure things out just to please you and won’t be as open or honest in their feedback.

- Encourage participants to ask questions out loud during research sessions. Avoid answering their questions to see how difficult it is for them to figure it out on their own. You won’t be there to help customers when they play them in the real world.

- Ask fact-based, non-leading, exploratory questions. For example, “describe how you can use this feature” or “what was the objective of the mission you just played?” Avoid opinion-based questions like, “Was the feature easy to grasp?”

- Look at everything as a whole when analyzing the results. Avoid highlighting only the part of the results that confirm your intuition. This is called “confirmation bias” and it can mislead you.

Learn More

Want to know more about conducting research well? Check out Interviewing Users by Steve Portigal for practical, easy to use advice on getting more out of your research sessions. Or join us this October for a one-day remote conference User Research for Everyone, featuring 8 of the most respected experts in the field.

Laura Klein is a Lean UX and Research expert in Silicon Valley who teaches companies how to get to know their users and build products people will love. She’s a Rosenfeld Media expert and author of UX for Lean Startups (O’Reilly). Her newest book, Build Better Products, is set for release later in 2016. Follow her on Twitter or subscribe to her blog and podcast at Users Know.

Whose Job is User Research? An Interview with Steve Portigal

Posted on

Those of us who conduct user research as part of our jobs have made pretty big gains in recent years. I watched my first usability test in 1995 then spent a good portion of the 2000s trying to convince people that talking to users was an important part of designing and building great products. These days, when I talk to companies, the questions are less about why they should do user research and more about how they can do it better. Believe me, this feels like enormous progress.

Those of us who conduct user research as part of our jobs have made pretty big gains in recent years. I watched my first usability test in 1995 then spent a good portion of the 2000s trying to convince people that talking to users was an important part of designing and building great products. These days, when I talk to companies, the questions are less about why they should do user research and more about how they can do it better. Believe me, this feels like enormous progress. Unfortunately, you still don’t see much agreement about who owns user research within companies. Whose job is it to make sure it happens? Who incorporates the findings into designs? Who makes sure that research isn’t just ignored? And what happens when you don’t have a qualified researcher available? These are tough questions, and many companies are still grappling with them.

So, I decided to talk to some people who have been dealing with these questions for a living. For this installment of the Whose Job is User Research blog series, I spoke with Steve Portigal, Principal at Portigal Consulting. He’s the author of Interviewing Users, which is a book you should read if you ever do any research on your own.

You still don’t see much agreement about who owns user research within companies.

Steve has spent many years working with clients at large and small companies to conduct user research of all types. He also spends a lot of his time helping product teams get better at conducting their own research. Because he’s a consultant, he sees how a large number of companies structure their research processes, so I asked him to give me some advice.

What Does It Mean to Own User Research?

“There are two aspects to ownership,” Steve says. “One is about owning the need. The other is about owning the actions where we build on what was learned in research. It doesn’t seem like there’s any perfect model for how research ownership works.”

As Steve points out, the concept of owning research is much more complicated than a single ownership model can describe. At a minimum, somebody needs to determine which business questions should be answered. Somebody needs to figure out how to get those questions answered. Somebody needs to figure out what to do with the results of the research. It’s not often the same somebody.

In fact, the different people involved in the research frequently are not even from the same department. Company org structures vary widely: researchers might be their own group or they might be part of marketing, product, or even engineering. The people requesting research and using the results might be product managers, ux designers, or marketers. That’s not even addressing the times when research is done by outside firms or by team members who aren’t trained in research.

There’s a reason this is so confusing. Despite the fact that various forms of user research have been used to develop products for decades, the widespread adoption of user research in the tech industry is still relatively new. Steve says, “People have more dogmatic theories about best practices, but I’m seeing so much variety and so much iteration as people try to figure it out.”

Hopefully with a few more iterations we’ll get a better idea of what works and what doesn’t. Although it’s likely there will never be one single answer. The best configuration may always depend on factors like company size, industry, and type of research that needs to be done.

Who Should Do the Research?

Despite the fact that Steve is a highly experienced research expert who conducts research for clients, he’s very upfront about the fact that internal teams should be heavily involved with the research. Often they should be doing it themselves. This is one of the reasons he teaches people how to be better at research and why he wrote a book that explains how to interview users more effectively.

Not every research study requires an expert at the helm. Quite a few products would benefit from having somebody on the main product team who could quickly get feedback or answers to simple questions. “Even a newbie researcher should be able to answer some factual questions about what people are doing or might want to do. They also have the opportunity to reflect on what assumptions they were holding onto that were incorrect,” Steve explains. “You’ll always get more questions to go with your answers, but hoo boy–it’s better than never talking to users and acting with confident ignorance.”

There are some questions you’re better off bringing in an expert, though. “The more help you need in connecting the business problem with the research approach and connecting the observations to the business implications, the more expert help you need,” Steve explains.

We should all know by now that things like usability testing make our products simpler and more intuitive for our users. There’s also a huge amount of information to help you run a basic usability test. But when you’re getting into some of the trickier questions around generating or validating business ideas–or turning early customer research into innovative solutions to problems, an expert can help guide the research process and make these complicated research studies run more smoothly.

How Do We All Work Together?

Of course, none of this answers the question of how we all work together. Steve feels like there’s not a single answer to this question, but it’s very important to decide this ahead of time so that everybody knows what to expect.

For example, consider where researchers live in relation to the people who need insights to inform product design. When your company has expert researchers, they may be part of an in-house silo, embedded in the product team, an outside consultant, or some hybrid of any of the above. Wherever they come from, you should determine five things as part of your research planning process:

- What do we need to learn?

- Who are we going to study?

- What will we do with the outcomes?

- How are we going to work together?

- How will we define success?

A standard predictor of success is how much the client is able to join the fieldwork.

“Negotiating these elements is part of what a good research person should be doing,” Steve says. “The team structures, the availability of stakeholders – these are all inputs.” In other words, there’s no one-size-fits-all when it comes to determining how research projects should happen.

According to Steve there is one constant: “A standard predictor of success is how much the client is able to join the fieldwork.” And he’s right. The best type of research is the research that people use to make better decisions. The more involved your team is with conducting the research, the more likely they will understand and pay attention to the results.

Learn More

Want to know more about conducting research well? Check out Steve’s book Interviewing Users for practical, easy to use advice on getting more out of your research sessions. Or join us this October for a one-day remote conference User Research for Everyone–featuring 8 of the most respected experts in the field.

Laura Klein is a Lean UX and Research expert in Silicon Valley who teaches companies how to get to know their users and build products people will love. She’s a Rosenfeld Media expert and author of UX for Lean Startups (O’Reilly). Her newest book, Build Better Products, is set for release later in 2016. Follow her on Twitter or subscribe to her blog and podcast at Users Know.

Product Teams – Who Does What?

Posted on

When we started talking about putting on the PM + UX Conference, the first thing we asked was, “What sorts of things should we talk about?” Since the folks at Rosenfeld Media are, not surprisingly, extremely user-centered, the obvious answer was, “We’re not sure. How about we do some research and find out what questions our attendees might have?” So we did.

The most interesting thing to me was that a lot of the questions people asked boiled down to “Who does what on a product team?” This was curious. I mean, we’re all working on product teams or we’ve worked on them in the past, right? Shouldn’t we know what our jobs are? Shouldn’t we know what everybody else is doing? Well, yes! We should! And yet… when I started to dig around and have conversations with people, I got very, very different answers about how things really worked.

That was odd. It turned out that, although we all have job titles like Product Manager or UX Designer, many of us have very different ideas about what it is that we’re supposed to actually do all day. Do designers talk to customers? What about PMs? Who decides what features go into a product? Who makes wireframes? Does anybody do usability testing? If not, could they please start?

Like any good team faced with more questions than they started with, we did some more research. Ok, first we had a couple of stiff drinks. Then we did some more research. I was volunteered to lead the way.

The Research Methodology

I wanted to make sure that we hadn’t gotten weird data or misinterpreted the questions being asked- after all, it was a survey – so I conducted several qualitative interviews with PMs and UX designers in various sized organizations. I asked about what PMs and UX designers did at their companies. Incidentally, I also got a lot of “but the way we SHOULD do it is…” answers, but I was focused on reality for the moment. And reality seemed just as confused as the survey results.

After talking to a dozen or so people, I decided I wanted to collect exactly what tasks were performed at different companies so that we could see how much overlap existed. To get as many data points as possible, I sent out a very simple survey asking people what their role was, which tasks they thought were performed by UX Designers and which tasks they thought were performed by PMs.

I got dozens of responses from people on different product teams–mostly UX, PM, and researchers–and even some engineers, marketers, founders and managers. Of these responses, I got hundreds of different things that are being done by product teams.I am not exaggerating. It seems that PMs and designers are performing a dizzying array of tasks from generative research to making roadmaps to managing stakeholders to visual design.

I got curious. Who on these teams are doing all of these things? Seriously, most product teams just aren’t that big, so how do they get hundreds of things done? Who’s got that kind of time?? I narrowed down all the responses by deduplicating things that were similar. I picked the things that were mentioned the most, narrowed it down to 73 discrete tasks or processes–which is still a LOT of things for a team to be doing.

Next, I did a card sort: I asked people to review each task and tell me whether it was mostly done by designers, mostly by PMs, done about equally, or generally done by nobody or somebody besides these. I also said you could make your own categories for things that didn’t fit.

I ran the card sort remotely using OptimalSort, which was handy, since that meant that I could gather a lot more input than if I’d had to travel around with a set of index cards and watch each person do the sort. It also made it a lot easier to categorize, and you’ll see in just one second why that was important.

The Research Results

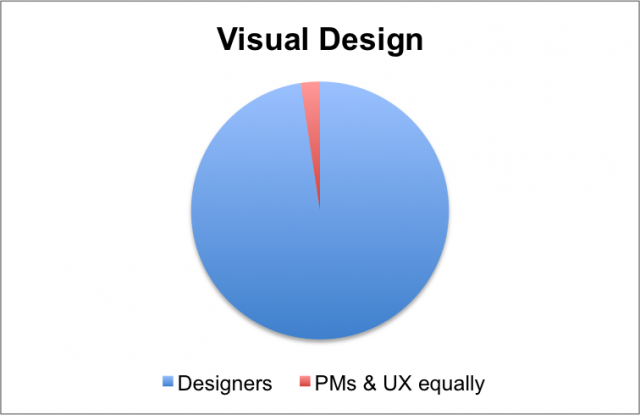

82 of you weighed in with how things worked at your company. And, surprise surprise, there was virtually no agreement. I mean, there were a few similarities. Everybody agreed that visual design was done by someone in the design department (except for those of you who said it was done by outside people or people in marketing). And almost everybody agreed that roadmaps were made by PMs. Or by execs. Or by managers. Or by someone else.

Oh, and nobody agreed about who was supposed to do user research, except that a lot of people made a category called something like “things we aren’t doing enough of” and stuck user research into it. So, that was fun.

Here are a few of the things people actually agreed on mostly.

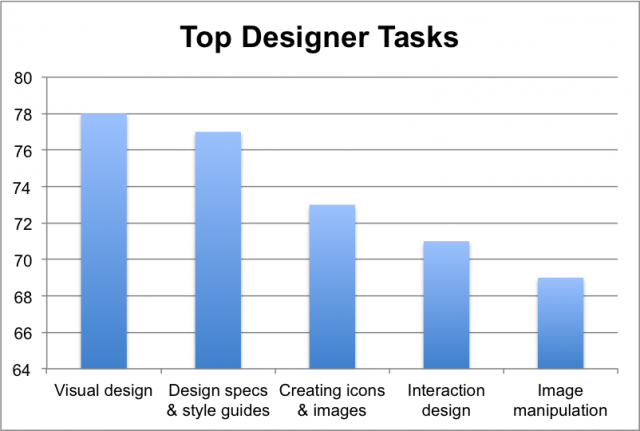

What Are Designers Doing?

Interestingly, there was far more agreement about what designers do than about what product managers do across companies.

Visual Design

The most agreed upon tasks were things like visual design, design specs and style guides, image manipulation, illustration, and branding. Almost everybody agreed that these were mostly done by designers.

The unfortunate part about this particular agreement is that, while it’s true that these are more “design” tasks than they are “product management” tasks, it tends to confirm the idea that many organizations still see design as limited to visual design.

Interaction Design

It has “design” right there in the title, but 10% of the respondents said that interaction design is done equally by product managers and designers, and one sad person said that it’s not being done at all.

Other Mostly Design Tasks

Other tasks that were mostly done by designers were what you might expect:

- Mockups

- Wireframes

- Sketching

- Site Maps

- Information Architecture

Interactive prototypes were also very high on the list of tasks mostly done by designers, although at a few companies they’re still being made by engineers or developers. This may reflect the huge number of new prototyping tools available these days.

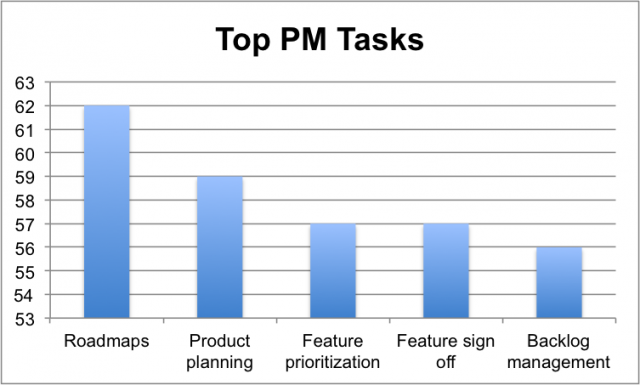

What Are PMs Doing?

There was a lot less agreement across companies about what PMs were doing, frankly.

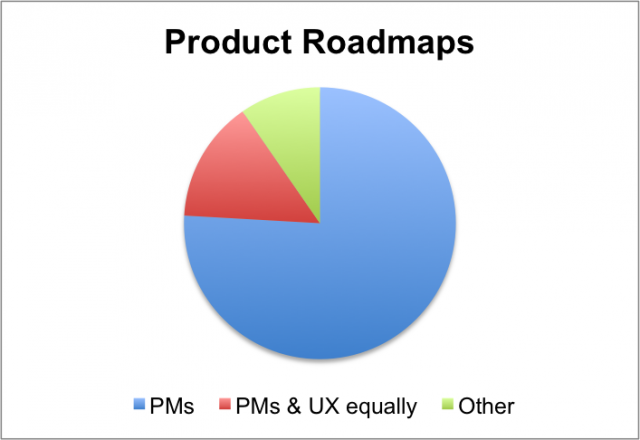

Roadmaps

The most agreed upon task for product managers was creating and maintaining feature roadmaps, with 63 people saying that this was almost always done by product managers. In twelve cases however, roadmaps were maintained equally by designers and PMs, and in six cases, they’re being made by someone else or not being made at all. Project and program managers are sometimes the keepers of the roadmap, but very infrequently.

Feature Definition, Business Strategy, and Scheduling

Many of the most common product management tasks, unsurprisingly, are things that involve defining and prioritizing features, creating revenue models, or project management and scheduling tasks like sprint planning.

But there were really only a few of these tasks where more than half of the respondents agreed that they were done mostly by product managers and there were no tasks where more than three quarters of the respondents agreed were all or mostly done by product managers.

Business strategy, for example, was reported to be done primarily by PMs in only 50 of the 83 cases. In five cases, it was done equally by PMs and Designers and the rest of the time was done by anybody from executives to finance to nobody at all. In one case, the entire team worked together on setting business strategy.

What are People Doing Together?

The most inspiring part of the study for me was how many tasks people are doing together – either as a whole, cross-functional team, or at least across the PM and Design roles.

In 13 cases, the entire team reported brainstorming new features together, and in 51 cases, brainstorming was done about equally by PMs and UX designers. Hopefully that means that more people are getting involved in figuring out which new features to build for users.

Perhaps the most evenly split task was customer discovery, which worked out like this:

- Mostly designers: 17

- Mostly product managers: 17

- Equally by PMs and designers: 20

- Not done: 15

- Other: 16

I don’t like to see customer discovery not getting done almost 20% of the time, but it’s good that when it’s happening it’s a shared task. Needs finding had a similar split, as did most forms of generative research. At least, when user research is getting done, it’s getting done by the whole team rather than being entirely run by one group.

Why Does this Matter?

Having a shared understanding of what we do and what we’re supposed to do is hugely important to creating a well-functioning team. Imagine trying to build a baseball team where nobody agreed on what shortstops were supposed to do or what made somebody a great pitcher. It would be chaos.

And yet, every day, we hire people, add them to our teams, and give them titles like product manager or UX designer or researcher, without realizing that the last company where they worked might have had an entirely different definition of the role. Then we’re shocked when somebody who was a fantastic PM at their last company isn’t succeeding. Or we can’t believe that the new designer can’t do what we consider to be a trivial task. Worse, sometimes we have no idea what our coworkers are doing or what they’re supposed to be doing, which is why important tasks can fall through the cracks.

Learn More

There is actually one more bit of research that I’ve been doing in parallel for awhile now as I work on my new book, Build Better Products (Rosenfeld Media ‘16). I’ve been talking to teams in order to understand which ones are most effectively delivering value to users. There seems to be a very strong correlation between good outcomes and the teams that report doing certain of these tasks together. Teams that conduct research together are more likely to understand their users. Teams that use that research to ideate together are more likely to come up with feature ideas that users want. Teams that decide business strategy together are less likely to get into arguments about what should be prioritized.

If you want to learn more about how your team can work together more effectively, check out the upcoming one-day online conference devoted exclusively to Product Management + User Experience. I’ll be sharing activities you can run yourself to build team cohesion and get everybody working together. Your ticket gives you all-day access plus recordings to the full program. There are only a few spots left. Hope to see you there!

Laura Klein is a Lean UX and Research expert in Silicon Valley who teaches companies how to get to know their users and build products people will love. She’s a Rosenfeld Media expert and author of UX for Lean Startups (O’Reilly). Her newest book, Build Better Products, is set for release later in 2016. Follow her on Twitter or subscribe to her blog and podcast at Users Know.

Whose Job is User Research? An Interview with Tomer Sharon

Posted on

This is part 2 in the series Whose Job is User Research.

As part of my ongoing series of posts where I try to get to the bottom of who owns user research, I reached out to Tomer Sharon, former Sr. User Experience Researcher for Google Search and now Head of UX at WeWork. He wrote a book called It’s Our Research which addresses this exact topic. His new book, Validating Product Ideas, is also now available. He’ll be speaking at the upcoming Product Management + User Experience hosted by Rosenfeld Media, designed to help teams work together to learn more about their users.

Tomer recently announced that UX at WeWork won’t have a research department and what drove that decision. I took this opportunity to ask Tomer a few questions, and to learn what suggestions he has for creating a team that conducts research well and uses it wisely.

Everybody Owns Research

Possibly the most important lesson you can learn from Tomer is this: stop asking the question “who owns research?” “Everybody owns research,” he explains. “Research is a team sport. What research is needed is determined based on different sources–decisions the team is trying to make, known knowledge gaps, dilemmas and arguments among and between teams and more.”

Research is a team sport. The team needs to decide what it needs to know together. – Tweet This

He encourages people to use all of these sources to generate research questions. For example, if a team has trouble deciding on development or prioritization of new ideas, then a research question might be “What are the top needs or challenges our users have?”

“Research questions are questions the team needs answers to, not questions that you ask research participants during a study,” he says. That means that the team needs to decide what it needs to know together.

By making research a key part of everybody’s job, it gets rid of the problem many teams have of ignoring research reports. Instead, research becomes a tool everybody can use to answer important questions.

Use Researchers as Facilitators and Coaches

Of course, that all sounds delightful, but it does bring up three important questions:

- What if people just don’t do research?

- Should we really let people who don’t have any experience do research?

- And the most important question (to researchers, anyway) is does this mean we don’t need actual researchers any longer?

There’s good news for researchers among us. We’re still needed, and we’re not just going to let completely untrained people take over our jobs! But instead of being a service organization, Tomer recommends that researchers become mentors, coaches, and facilitators of research. WeWork’s UX team will still have well trained research professionals. In fact, those are some of the first hires that Tomer wants to make. The difference is that they will be embedded with product teams and work with everybody to help make sure research is conducted well instead of working alone in their own silo.

Of course, there are a few types of studies that professionals should lead. “In 90% of the cases,” Tomer says, “I’d prefer a non-researcher doing research, supported by guidance and mentorship of a researcher. The remaining 10% are studies such as ethnography, surveys (yes, surveys), and highly complex quantitative studies, in which I’d prefer a researcher leads the project.”

Other times when you may need to bring in specialized researchers include cross-cultural studies: where you learn about the behavior and needs of people in a culture very different than yours. If Tomer needs to learn about the needs of WeWork members in China or Indonesia, he partners with a local design research agency (not a market research agency!) to make sure the study runs smoothly and gets insightful results. But even then, all the team stakeholders must be directly involved with the research. Learning about your users isn’t something you should outsource.

Learning about your users isn’t something you should outsource. – Tweet This

Turn Research Directly into Design

Here’s some more good news for those of you who don’t enjoy writing twenty page research reports that are never read (or creating hundred slide Powerpoint decks that colleagues suffer through). Making research an integrated part of the design process gets rid of the deliverables step.

“Research must lead to design that then leads to more research,” Tomer explains. That’s why his favorite method of synthesis and communication is the design studio or design sprint. During a design sprint, the team comes up with a shared understanding of research outcomes and their design implications through sketching, critique, and quick research on team solutions. “The researcher or key decision maker in the team or company can facilitate a discussion in which the answers to the research questions are shared.”

Research must lead to design that then leads to more research. – Tweet This

In other words, get rid of the Powerpoint, and focus on rapid synthesis of research results. Immediately turn them into ideas and designs. This can save you weeks of report writing, and it also means that your team gets a clearer idea of the problems that you’re trying to solve.

Break Down Silos (even if it’s not your job)

Obviously this is all easy for Tomer to say. He gets to build the WeWork UX team from the ground up. But what about those of us who work in companies where research is off in its own silo? Do we have to wait until we’re in charge so that we can change the rules?

Tomer offers insight on this_having spent a lot of his career working at a very large company with a very large research group. “Talk!” he says, “Approach new hires and help them with something not related to research. Teach them how to find the best parking spot or how to change their profile picture on the intranet. The key here is trust and relationship building. From there, mountains can be moved and silos can be brought down.”

Even if we’re put in silos by management, all of us, whether we’re researchers, designers, product managers, or anything else, can reach out to our coworkers and build teams that transcend silos. It’s not easy, but the results are worth it, since we end up with better team communication and products that solve a need for our users.

Learn More

Check out Tomer’s book Validating Product Ideas: Through Lean Research. Or join us on October 11 for our one-day remote conference User Research for Everyone, featuring 8 of the most respected experts in the field.

Laura Klein is a Lean UX and Research expert in Silicon Valley who teaches companies how to get to know their users and build products people will love. She’s a Rosenfeld Media expert and author of UX for Lean Startups (O’Reilly). Her newest book, Build Better Products, is set for release later in 2016. Follow her on Twitter or subscribe to her blog and podcast at Users Know.

Whose Job is User Research? An Interview with Jeff Gothelf

Posted on

While doing research for the upcoming PM+UX Conference, several respondents requested guidance around how user research should managed. In fact, it was the most common write-in answer on our survey, and a question that comes up repeatedly whenever I give talks. Apparently, there seems to be very little consensus about who on a product team should own research. This makes it a lot harder to get user insights and make good product decisions.

Jeff Gothelf is co-author of Lean UX and Principal at Neo In a way, this is good news. Five or ten years ago, there would have been more questions like, “How do I get my boss to consider doing user research?” and “What is user research good for?” Those still come up, but far more frequently, I’m hearing things like, “How do we make sure that everybody on the team understands the research?” and “Who is in charge of making sure research happens and deciding what to do about it?” Research, these days, is assumed. It’s just not very well managed.

To answer these questions, I interviewed several very smart people who know a thing or two about research and building products. I’ll share some of their suggestions in a series of blog posts.

First, I spoke with Jeff Gothelf, the author of Lean UX (O’Reilly, 2013) and Sense and Respond (Harvard, 2016).

Jeff spends most of his time training companies around the world on how to build usable products using Lean user experience design techniques. He’s seen his share of different organizations, and has an excellent sense of which ones are building the right things. So I asked him to help me figure out the best way to incorporate user research into the development process.

User Research is Owned by the Team

Companies that are functioning well and building great products are doing user research. And they’re doing it together. “Research is owned by the team,” Jeff says. “It is as important as design or writing code. That said, in most organizations, it’s the UX person who typically drives the research or, in their absence, the PM. It’s not necessarily the best approach, but it’s what I see most often.”

In this model, the person responsible for making sure that the research happens doesn’t own performing or communicating the research. What this means is that the product manager or UX designer will request that some specific research will be done.

Unfortunately, this often translates into the PM asking for research and a researcher who is completely unaffiliated with the team or even hired from outside going off and interviewing users and then coming back six weeks later with a report, by which time the team has almost certainly moved on. This generally means that the results of the study will never be used by the team, since the results will be out of date and irrelevant.

Create a Better Scenario

Rather than seeing research as something that is simply requested by someone on the team and then delivered, Jeff suggests a more collaborative approach. The best case involves the PM or UX designer sharing a specific business or user need that requires some research, and then having that turn into a shared activity where members of the team are involved in performing the research. “I’ve found it rare that a team can’t execute their own research,” Jeff says.

“I’ve found it rare that a team can’t execute their own research.” – Jeff Gothelf – Tweet This

There’s still a place for experts in Jeff’s model too. “There may be some situations where getting to the participants or communicating with them may prove challenging (language barriers, cultural differences, etc.) in which case an expert can help,” Jeff explains. “Also, if nobody on the team has research experience, bringing in an expert to train the team is helpful. If you already have some researchers in the company, they can train and deputize others to start collecting user insights.”

Never Outsource Research

Jeff is also not a fan of having outside researchers conduct studies, since it takes time and can lead to a one and done mentality. “I advise teams to never outsource their research. Letting someone else do your research means waiting for them to do it, synthesize it and write it up. Also, outsourcing the research typically means it’s a singular or at least a finite event. I believe research should be continuous.”

When teams bring outside people in to conduct studies and simply hand off results, they’re missing out on a huge opportunity to build skills within the team. Outsourced studies, even relatively simple ones, can cost thousands of dollars. If you’re making that budget decision every time you want to learn something, it’s going to keep you from doing all the research you should be doing. On the other hand, if members of your team can find ways to learn constantly from users, that price comes down considerably, as does the time it takes to run a study.

Finding ways to learn constantly from users brings the price of research down considerably. – Tweet This

There are a lot of options for getting your team up to speed: outside experts can come in and facilitate training sessions or work with the team to do the research rather than perform everything for them. Jeff also recommends Steve Portigal’s book, Interviewing Users, Giff Constable’s Book, Talking to Humans, and my own book (Thanks, Jeff!), UX for Lean Startups.

Get Out of Silos

Cross functional teams make many Lean UX practices possible. It’s easier to have “the team” be responsible for customer discovery if the team exists as a persistent entity throughout the life of the product. But the reality is that many companies still don’t work that way. Research, product, design, and engineering are often in their own silos, communicating only through deliverables, if at all.

The best approach is to get rid of silos entirely, but very few of us have the option to restructure how our companies work in order to make research more effective. If you’re in an organization where research has its own silo, Jeff has several suggestions for making those silos less restrictive.

“Brown bags, demos, ride-alongs, workshops – these are all good tools to show how to do research and what to make of your findings,” he explains. “At the same time, the PM/UX folks should seek this out from their researcher colleagues if it’s not offered up.” Even when your company is divided up by practice instead of by product team, there’s no reason why you can’t reach out to other people working on similar things and build bridges between the silos.

Learning what other people do and how to do it and teaching them what you do and how you do it can be a wonderful way of creating respect and unity within the team. It has the added bonus of making the product better because everybody ends up working together rather than stepping all over each other and ignoring real customer needs.

Learn More

Interested in helping your teams collaborate to create better research outcomes? Check out Jeff’s book Lean UX (O’Reily, 2013) or join us this October for a one-day remote conference User Research for Everyone, featuring 8 of the most respected experts in the field.

Laura Klein is a Lean UX and Research expert in Silicon Valley who teaches companies how to get to know their users and build products people will love. She’s a Rosenfeld Media expert and author of UX for Lean Startups (O’Reilly). Her newest book, Build Better Products, is set for release later in 2016. Follow her on Twitter or subscribe to her blog and podcast at Users Know.

Build Better Products

Posted on

Nobody wants to build a bad product. Many of the worst products in the world took an enormous amount of time, energy, and money to create. People cared about those products. They worried and argued and worked hard and were probably excited when their product finally made it out into the world. Imagine how awful it felt when nobody wanted what they made.

Or maybe you don’t have to imagine it. Maybe you’ve been on a team that’s shipped a product that wasn’t useful or usable. Maybe you even led it.

Making great products is incredibly hard to do. I’d like to make it a little bit easier. That’s why I’m writing Build Better Products.

Build Better Products is a book for product managers, entrepreneurs, and anybody else who makes decisions about products. But it’s more than just theoretical hand-waving. It’s a step-by-step handbook to help teams create a product development process that incorporates the best of business strategy, customer empathy, user centered design, and objective metrics. It includes exercises developed during workshops with real companies and secret product development tactics from some really amazing surprise guests.

It’s also not done yet. I’m hoping to have it published in 2016, but I’ll be sharing bits as I go along and asking for feedback along the way. I hope that you’ll help me make it even better.

Author Archives: Laura Klein

The latest from Rosenfeld Media