-

The letter begins, “You may have read in the newspaper–or heard on the radio or television–the official government figures on total employment and unemployment issued each month.” (The writer of the letter added to em-dashes to make sure we notice they are using new-fangled media channels. I assume the template for this letter was written in 1992 or something, since the Internet isn’t mentioned. There is no actual date on the letter.) The letter goes on to say, “We have selected your address and about 55,000 others throughout the United States for this survey … your participation in this voluntary survey is extremely important to ensure the completeness and accuracy of the final results. Although there are no penalties for failure to answer any question, each unanswered question lessens the accuracy of the final data. Your cooperation will be a distinct service to our country.” There is no explanation how to opt out, just an address to send comments. I didn’t want to opt out, though. I figured this opportunity is just like the time I was a Nielsen TV ratings household where I didn’t own a TV. This opportunity is similar because I don’t work for a company. I could be another statistical outlier that the analysts would have to contemplate … and probably throw out.

But what gets me is those adjectives (or noun-ified adjectives) in the letter. “Official,” “important,” “completeness,” “accuracy” (twice), “final” (twice), “distinct.” These are the adjectives that we have been fed for decades about surveys. Sure, I took my statistics courses in university–even worked as a teacher’s aide for one of the classes–so I respect the math and the statisticians. I don’t respect the people who write the survey. Their use of English is imprecise, which leads to crazy results. In addition, the Bureau insists on conducting the surveys in person, by voice. Your answers or side-chat with the human carrying the survey don’t influence how the answers are worded, and nothing matches up with reality. They ask for details you don’t know about other household members. Nothing is actually accurate, because they are using a survey to capture the information.

So, these two very normal 60-year-old ladies turn up at my front gate this morning. I was in the middle of my bike workout in the garage, so they weren’t interrupting my work, at least. They showed me their ID’s, handed me another copy of the letter, and introduced themselves as the Field Rep and her Supervisor. I got the feeling the Field Rep was on her first week of this survey-thing. I chatted with them cordially about where in the Bay Area they live while changing out of my bike shoes and invited them in the house, offered a cup of tea–everyone was smiles. They told me how not all the survey participants are so cheery and cooperative. They only accepted water. (I bet there’s a rule about what they can accept. I know there’s a rule to observe when I ask government employees to participate in an interview: I can’t give them any individual compensation. Group compensation is okay in some places, like a basket of muffins or something. A coffee cup, a check, a baseball cap–those are forbidden. No bribery implied.) Then the little gray laptop came out, and thus began three things: the circus of trying to get the laptop to behave the way the Field Rep intended, the defining and re-defining of the English used in the survey, and the hand-waving about what answer to put down, all resulting in the increasing unease of the Field Rep herself. I didn’t mean to, but I think I ruined her day.

1. The Circus of the Laptop

The survey began with all the traditional questions: is this your primary place of residence? What is your name? Who else lives here? What is his name? When I answered, “Philip” for that last question, at least the Field Rep had the presence of mind to say, “So I assume his gender is male.” That’s the only time she “slipped up” and allowed normal human discourse to dictate one of her answers. I asked about the rules of conducting the survey, and her Supervisor said they are required to read each survey question exactly as it is printed. And they have to read the answers out loud, too. Except the household income question. That struck me as humorous, because the Field Rep swung her laptop around to show me a list of radio buttons, each with an income range next to it for the household. I grinned and said, “We’re number sixteen on that list,” playing along with her. I guess it’s taboo to say income figures out loud.

But when we got to the question of race/ethnicity (I forget the actual wording on this one), that’s where we ran into trouble. Ever since participating in my first census as an adult in 1990, I have filled in the circle next to “Other” and hand-written “human” on the blank line next to that. I have a personal philosophy that paying attention to non-affective differences only perpetuates discord. I’ve not read anything yet that clearly correlates someone’s ability with their family tree. There’s a lot that goes into ability: nature, nurture, being in the right place at the right time, even love of doing something, as Malcolm Gladwell espouses. I remember taking an aptitude test in high school. Sitting in the chair next to me was my best friend, whose last name also happened to be Young. We called ourselves twins, even though we weren’t related. I remember feeling mortified that, when I looked over at the front cover of her test booklet, I had one bubble filled out differently than hers. Race. She’s descended from people who came from China six generations ago. I’m descended from people who came to California six generations ago from Canada and Europe. My best friend and I were twins to the core, so why did this stupid test booklet cover declare that we weren’t? I remember trembling I was so upset, right there in the classroom where they gave the high school aptitude test. So, my personal philosophy about this is pretty strong. And when the poor Field Rep asked, I instructed her to just choose the “Other” radio button. She read the possible answers out loud, and the only place the word “other” appeared was as “Other Pacific Islander.” She tried to skip it, but the survey software defaulted to “Latino.” The Supervisor stood up and came to bend over the laptop with the Field Rep. They took a few moments to figure out what they could do. The Field Rep looked up. “Is it okay if I just mark down “Caucasian” for you? Nope. It’s not okay. I make eye contact with the Supervisor and smile. She keeps a straight face, trying to hide that I’ve made her feel uncomfortable. The Supervisor pointed to something and they clicked, relief flooding their faces. I have no idea what they did, or how my answer was recorded. I smiled and chatted about how software sure isn’t designed well.

Imprecise English

The next part of the survey asked about my type of work. The first question was, “Do you run a business or a farm?” I laughed, because of all the possible things a person could do for a living, why pick just those two to begin with? I have a veggie garden but I don’t sell the produce, so I figured “farm” meant “selling produce” and I opted out of that one. But “business?” To me, that means I run an agency or a shop or a firm–something with employees and a location. I don’t have any employees, and I do my work in my living room, or on the ferry, or at the airport, or in client conference rooms. I didn’t think I was a “business” either, so I explained this to the Field Rep. She asked, “Do you work for someone else?” “Yes,” I said, “for my clients.” She shook her head, “No, you run your own business.” Okay. There is is. “Running a business” equals “not a W4 employee.”

“So, describe what work you do,” the Field Rep asks next. I pause, for a long time. You know why–how do we explain this field? How do we put it into a couple of words that have meaning in the traditional sense of “what do you do for work?” If I’m a mechanic, I say, “I fix cars.” If I’m an ex-software engineer trying to encourage big corporations, governments, universities, and start-ups to go talk to real people before investing in a product or service that might flop, I say, “Um. Uh.” The Supervisor, having heard my chatter about what I do before the survey started, tries to help, “You do software?” I try to un-fumble myself, saying, “I actually do research, and analysis, and …” The Field Rep starts typing in my response. She says out loud, “Researching, Analyzing … what? Analyzing what? They like ‘ing’ words.” Ech! My eyes roll up for half a second, as she has pressed another soapbox button on silly old me. It peeves me when people make verbs into gerunds by adding “ing” to them. It weakens the verb, makes it into a noun that can be boxed up and kept at a distance rather than tasted and experienced as an action. “I research and I analyze the data I collect.” I hear myself saying, “I hate gerunds.” Eek! Sorry ladies–am I turning into one of the uncooperative survey participants? Anyway, I finally concoct a sentence in my head that I’m willing to have recorded on the survey. “I understand people in real life situations so we can design products and services to support them.” The Field Rep types it in slowly. “Whoops,” she says toward the end. “We’re out of room.” I wonder how much of my explanation fit in the box.

“For the week of December 5th, a Sunday, through December 11th, a Saturday, how many people did you do work for, including part-time and evening?” I immediately wonder if having two clients last week counts as two jobs. I ask about this. The Field Rep tells me, “No, you count all your clients as one job.” Good to know.

Then the special just-for-this-week section of the survey begins. It’s a sub-survey by the Department of Agriculture wondering whether I have had enough food to eat since last December. I’m still not clear on what their scope of research was. They wanted to talk to the person who does the shopping and cooking for the household. I was stumped on that one, because Philip does most of the shopping, and I do most of the cooking. “The person most knowledgeable about food,” they amended. Well, we had just finished outlining how Philip got his Masters degree in Plant Science. “He’s technically more knowledgeable about food, but maybe I could answer for us both?” The ladies laughed politely, and I wondered why the survey writer assumed that a person shopping also does the cooking–that those two chores are always only done by one person. The survey writer must not have any idea of the mathematical properties of the word AND. Alas. (It means if shopping is true and cooking is false (in Philip’s case), then the answer is false. If shopping is false and cooking is true (in my case), then the answer is still false. It’s only a true answer if both shopping and cooking are true, which is not necessarily the case for anyone in our household.)

Another of the questions was about whether I or another household member (meaning Philip) had shopped at a grocery store or supermarket last week. “Does Trader Joe’s count?” I ask jokingly. “Philip does the shopping there. I do that shopping at the farmers market.” The ladies do not smile. “How much did you spend there last week?” I don’t know, maybe around $40, and I explain he has a bowl full of receipts that I can rummage through if they want me to. Yes, they want me to. To simplify things, I just grab the top receipt from Trader Joe’s. Later, I remember he went to Target last week for his monthly stock-up on his favorite cereal. I didn’t feel like really looking for all the Trader Joe’s receipts from last week, and I didn’t want to paw through his stuff and find other receipts from Carl’s Junior or Burger King that I really didn’t want to know about. That’s his business, not mine. So I brought the receipt back to the table. “Fifty dollars.” I hold out the receipt. The Field Rep looks doubtful. The Supervisor says, “Hey, you were pretty close!” I read the total at the bottom, “It actually says $49.59, but I think you want to round up for these surveys, right?” The Field Rep continues frowning. She asks, “Have you bought food elsewhere …” And I interrupt, repeating, “I shop at the farmers market. Every Thursday.” “… at a butcher, a bakery, a produce stand, or a convenience store? A convenience store is like a 7-11.” I look at her. She suggests, “Maybe a farmers market is like a produce stand?” The Supervisor says, “They have produce stands in Fresno,” (or was it Modesto?) from which comment I deduce that’s where the survey writers work. “Let’s put down ‘yes’ to this one.” I look at the Supervisor and muse out loud why they don’t have farmers market in the answer set, and was this survey written 15 years ago? The Supervisor laughs and says, “It’s because the programmers are antiquated.” I think she means the survey writers. In Fresno. Or Modesto. I begin to wonder if she has hung out with them, to begin to know that they’re “antiquated” in their thinking patterns. I agree with her thinking, then realize she said that just to agree with my musings, which are growing darker because this line of thinking only illustrates how much the world view of the survey writer influences the results coming out of the survey.

The final Department of Agriculture question makes me laugh, because the wording is so cunning. I actually feel impressed by the writer. “Have you had enough money to buy the foods that you have wanted to eat in the past year?” Yes, that’s what you read: “Wanted to eat.” It just works on so many levels! The writer adroitly steps around the guilt and (resulting prevarication) a participant might feel if the question asked about basic food groups or foods you needed for basic nutrition. If a participant lives on coffee and hamburgers, this question works just fine. There were five answers, varying from getting all the food you wanted to eat to getting very little food you wanted to eat. I could have said I was not getting enough chocolate cookies or brownies to eat, but I decided to go with the first answer. I get enough food, yes.

Fooling with the Answers

The third thing that really left me with a need to write this essay is that none of the answers I gave were precise. Quite a few of them were guesses or “close-enoughs.” If the statisticians are using the data from 55,000 U.S. households to calculate the official, important, complete, and accurate final results, and 55,000 real-live, human, unique participants are approximating numbers and shrugging their shoulders about which radio button to select, then how helpful is that information?

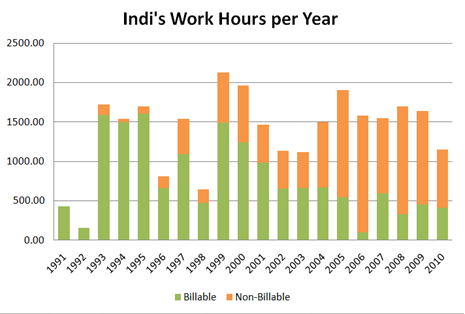

Here are some examples. One question about work asked how many hours I and the other household members worked last week. “Do you mean billable hours, in which I profited, or just all the hours I spent working on the computer? I also write and create workshop materials for various conferences I attend.” They are silent, pondering this. I walk across the room and grab my laptop from my desk, set it between the Field Rep and the Supervisor, and show them my spreadsheet. For the past two decades, I have recorded data in 15-minute increments about what projects and articles I’m working on, or if I’m “networking” or “reading” materials germane to my industry, or having “sales” calls, etc. I have twenty spreadsheets with this data, one per year since 1991. I am a bit of a data junkie. In last week’s column my spreadsheet shows I worked 10.5 billable hours, 0 sales hours, 12.75 hours doing stuff like maintaining my computer, touching base with people, reading articles, and commuting to a holiday party, 2.25 hours on this blog, and 2.5 hours making arrangements for speaking and teaching workshops. That’s a total of 28 hour last week. “Since this is less than 35 hours, is there a reason you did not work full time last week?” the Field Rep asks. I cannot resist musing out loud that there is a judgement in that phrase “did not work full time” and a strange cut off where something like 34.5 hours does not qualify as full time. I was surely at my computer doing work every day. I just don’t count the 15 minutes every hour that I spent writing to a friend or looking for a Christmas gift for my nephew. People who are employees also write to their friends and buy gifts for their nephews, surreptitiously, but it gets counted as “full time.” I admit I shouldn’t have reacted emotionally to the fact that my careful accounting cast aspersions unto me, but I did react. I think the ladies realized it, too.

If the statisticians could get their hands on my spreadsheets, they’d probably be thrilled. If they could just get information from payroll data, they’d be happy. Instead, they have to coax imprecise data from participants through the gauzy medium of a spoken survey.

(Note that the data is incomplete for the years 1991, 1992, 1996, 1997 and 1998. 2006 is the year I wrote my book.) “And how many hours did other members of this household work last week?” Um, how should I know what hours Philip put in? He works as a biochemist in a lab testing samples and reporting results. He’s at work a lot, so I guessed 45 hours for last week. They were doing fewer experiments because they had just moved the lab to a new room and were still setting up equipment. I have no idea how he logs his hours. We never talk about it. I guess we will now. (Note: I asked last night, and Philip says he recorded 37.5 hours last week on his company time sheet, which is 40 hours minus his 30 minute lunch each day.)Another example was the question, “How much could you save a month on food items?” I explained that I don’t look at food prices, I just buy what is locally grown and fresh and in season. I don’t know what the other version of this would cost at the grocery store. I never look. So I guessed $15. Shrug. Who would know how much they could save, anyway? What an odd question. What were they after?

Then the Field Rep read a question about household members buying food from a list of places that included vending machines. I never buy from vending machines, but I have no idea whether Philip does. The subject has never come up in the 11 years we’ve been together. So I had to guess about the answer to that question, too. Sorry, Department of Agriculture.

Oh, and I forgot. After the ladies left, I realized last week I had placed a $100 order for 65% chocolate chips from my favorite vendor, Sweet Earth in San Luis Obispo. I buy in bulk, 10 pounds at a time. Mint says I’ve bought these chocolate chips in bulk every other month. I forgot to mention it because the Department of Agriculture sub-survey never asked about online food purchases. I had totaled about $116 in food spending last week for the survey, which would average to around $550 a month, $1100 every two months. (Mint says this is about average for the U.S. participants that have signed up for their service.) The Department of Agriculture is missing almost 10% of my food spending by omitting online food purchases.

What Are the Numbers About?

In the end, all this effort that participants, field reps, supervisors, statisticians, and everyone at the U.S. Census Bureau put in adds up to … what? The letter says, “total employment and unemployment issued each month … estimates of the number of people working … help direct programs … and … provide … summary information about … participation in various government programs.” The letter says they include retirees as participants, and obviously they include the self-employed, since they are asking me to participate. I wonder how this particular collection of guesses and approximations got started. Who needed to know what, exactly? Is this question still valid today, or is the process/program self-perpetuating? I know one thing for certain: when I hear that monthly unemployment figures are up or down, I won’t pay any attention. It’s a statement based on 55,000 people waving their hands and rolling their eyes.

I have another seven months to look forward to participating in this survey. Giving my important and accurate guesses to the individuals at the Census Bureau (who are not bold enough to improve this data-collection project) is my distinct honor.

(I ought to state here that by the end of their visit, the supervisor thanked me and gave me some very nice compliments while the Field Rep turned gray-faced and made an abrupt dash for the front door. I was not sure how to react. I started apologizing, as if my musings had been too much for her, but perhaps she was only hungry. After all, they showed up at 11:45am and left an hour later. I did hear the Field Rep’s stomach grumble. I don’t think they had expected me to be at home, available to participate immediately. Hopefully she was just hungry, and wasn’t worried sick about the next time she has to talk to me.)

Who Can Believe the U.S. Unemployment Figures?

Posted on | Leave a comment