And you who wish to represent by words the form of man…relinquish that idea. For the more minutely you describe, the more you will confine the mind of the reader, and the more you will keep him from the knowledge of the thing described. And so it is necessary to draw…

—Leonardo da Vinci, 1487

I think about this a lot. This is Leonardo, one of history’s greatest thinkers, telling us that just talking is a bad way to describe an idea and often obscures its real essence. Leonardo is worth listening to. Here is the guy who invented the parachute, designed the helicopter, architected fortresses, engineered never-before-seen machines of every kind, and knew more about human anatomy than most doctors do today. And he also painted the Mona Lisa.

What would Leonardo think of the way we’re taught to think today? He’d hate it. Modern education tells us we’ve got to become linear A-B-C specialists: if we want to engineer, we study calculus and computational fluid dynamics; if we want to design, we study human factors and heuristics; if we want to paint, we study painting. But Leonardo studies all these things—and he came up with new solutions to old problems every day. What did Leonardo know that we don’t?

That is what Kevin’s book is really about. If we want to fully describe an idea, we must both write it and draw it. Kevin calls this “comics,” but I suspect that Kevin knows his term is a smokescreen. What Kevin is actually telling us—and showing us—is something far deeper and more powerful. It’s this: drawing is the secret to thinking.

Language teachers, standardized test-creators, education experts, journalists, and most recruiters disagree. “Words,” they say, “are the sign of intelligence. Just look at our greatest thinkers. Did they draw? No, they wrote! So learn your grammar, learn your five-paragraph essays, and shut up about your silly comics.”

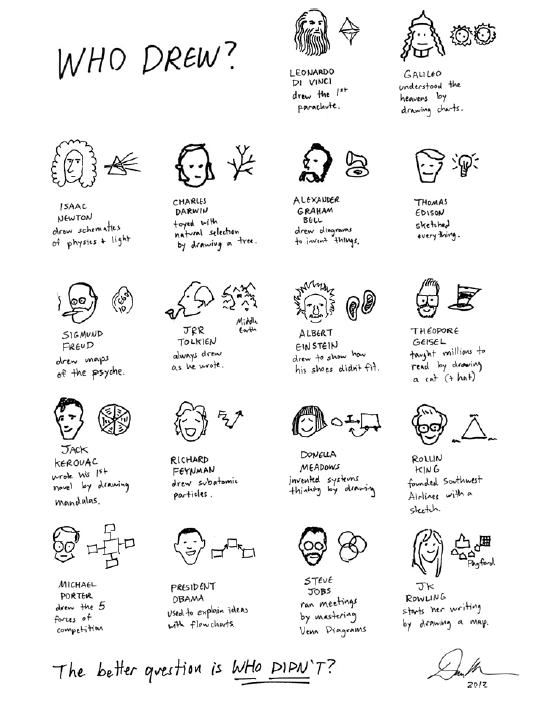

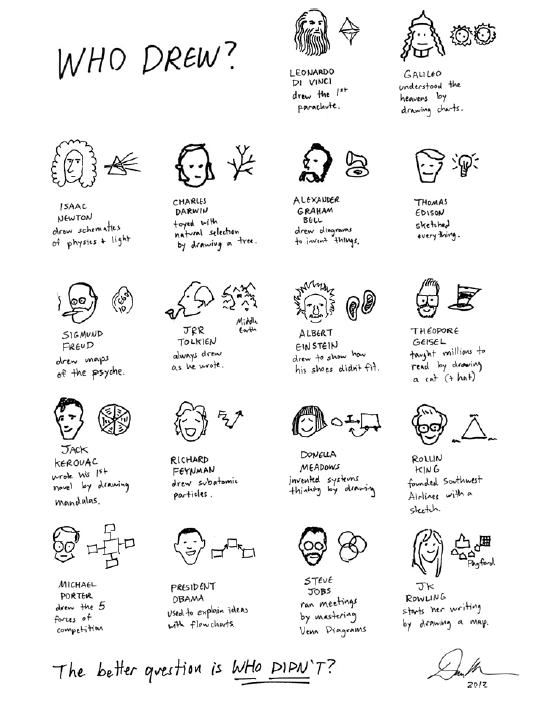

Anyone who tells you this is either lying, ignorant, or insane. Let’s take a closer look at our greatest thinkers and see how they really thought. It comes as no surprise that many thought with pictures: Newton, Euclid, Descartes, Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, Einstein, Galileo, and Steve Jobs. They all drew. But we knew that.

But what about the writers, the philosophers, the historians—you know, the real thinkers? They didn’t draw. Or did they?

Guess what: it turns out that most great thinkers drew—even though we’re never taught that. Darwin first explored the idea of natural selection by drawing a tree. Jack Kerouac wrote his first novel by drawing his concept out as a mandala. J.R.R. Tolkien couldn’t write without first drawing maps and portraits of his characters. Even J.K. Rowling just said that the first thing she did when she started to write her latest novel was to draw a map of the town in which it took place.

As Kevin says in the following pages:

Through some invisible societal pressures, the kids learned that the label of “artist” carried with it some minimum level of talent. In reality, I’d suggest that you’re an artist whether you call yourself one or not. So long as you can draw a stick figure, you’re well on your way to being able to create simple stories that explain your ideas better than any well-crafted words could.

Kevin, you are so right! Thank you. Now show us what you mean.

—Dan Roam, author of The Back of the Napkin and Blah Blah Blah

San Francisco, October 2012