There comes a time in every professional’s life when they wish to make a model.

This may sound silly at first glance, but as you dig into a body of work by any prolific thinker, you’ll see attempts to organize that knowledge in order to clarify the problem they are studying.

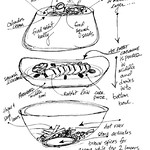

Darwin drew rambling tree diagrams as he contemplated the origin of the species. Zaha Hadid sketched, but you would expect that from an architect. Grant Atchatz and Michel Bras, renowned chefs, both made simple models of their complex dishes. Marie Curie and J.K. Rowling did, too.

Sometimes a thinker will attempt to represent a model with words, a “dancing about architecture” attempt. When people say that all teams need three things: someone who knows about business, someone who understands the customer, and someone who understands how to make things, you are hearing about a model. You might picture it in your head as a Venn diagram or a three-legged stool, because it is a model.

Some thinkers will tentatively draw something—helped along by the proliferation of tools, such as PowerPoint’s SmartArt. Steve Blank, the “father of modern entrepreneurship,” made this diagram to explain how one finds customers. The ideas are good, but the execution leaves something to be desired.

Of course, academic papers are full of terrible charts and diagrams.

I was in the thick of this problem when I started running workshops on social software design. I knew what I wanted people to consider when they added social features, such as forums or commenting. But I couldn’t make a model, which was shocking to me, because I am an art school graduate. Yet drawing is not the same as modeling. I took Karl and Stephen’s workshop on “Design for Understanding” in 2014. Karl was the academic who knew why things worked, Stephen was the design expert who knew how to make things that worked, and I was the lucky ignoramus who got to ride along (after all, ignorance is curable.)

The last few years have been filled with discussions, in the real world and online, as we pieced together the mysteries of why some things are good and some things are not, why things are the way they are. And I was the lucky one who got to read the book you are now holding in its many stages, from fumbling in the dark to shining a light on the problem. Through my conversations with Karl and Stephen, I learned that we don’t think with just our brain, we think with our bodies and our environment as well.

This journey to understand how we think has paid off for me. It helped me understand why some teams fall apart and some don’t, so I could write my book on teams. It gave me a way to teach students at Stanford to design more effectively and think more clearly. You are at the start of your journey, and as the cliché goes, I envy you.

This book is full of ideas, big and small, theoretical and practical. When you are done, you will not only speak a new language, but you’ll be able to dream in it. And best of all, there are plenty of pictures to help you understand. Pictures are not just for children—they are for anyone who wants to engage more of their mind.

I agree with Alice: “What is the use of a book,” thought Alice, “without pictures or conversation?” (Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland)

Figure It Out is both, and it is a supremely useful book.

—Christina Wodtke, author of Radical Focus and The Team that Managed Itself and lecturer in HCI at Stanford University