Eye tracking has always seemed very promising. After all, in our profession we spend a lot of our time trying to read users’ minds. One of our most powerful tools—usability testing—consists simply of asking users to think aloud while they use our products so that we can understand where they’re getting confused. I describe it as trying to see the thought balloons forming over users’ heads, especially the balloons that have question marks in them. They’re the ones that tell us what needs fixing.

Eye tracking is naturally appealing to us because it holds out the promise of another window into the mind: the semi-magical ability to know what people are looking at. And since there seems to be a strong (though not absolute) connection between what people are looking at and what they’re paying attention to, eye tracking can provide another set of useful clues about what they’re thinking and why the product is confusing them.

At the very least, it promises to answer questions like “Did they even see that big button that says ‘Download?'” If the eye tracking shows that people aren’t seeing it, then we know that they can’t possibly act on it, and we should probably give some thought to making it more prominent somehow.

That’s why eye tracking is one of the three technologies I’ve been waiting for, for a long time.1 In fact, when I wrote Don’t Make Me Think, it was going to be based in part on some eye tracking research I was going to do. But it turned out that the technology at the time—particularly the software to analyze the mountains of data that eye trackers produce—just wasn’t up to the task. Fifteen years ago eye trackers were for specialists who spent all their time feeding them their specially prepared fuel pellets, writing their own analysis software, and trying to read the resulting runes.

Then came the millennium and a quantum leap forward by the manufacturers. All of a sudden, instead of requiring programming skills, bailing wire, and a soldering iron, eye trackers worked right out of the box. And they came with software that let almost anyone—anyone with $30,000—generate impressive output, especially (God help us!) heat maps.

Over the years, I’ve sat through countless demos and presentations, and tried to read everything that was written about eye tracking and UX. At one point, one of the manufacturers was even nice enough to give me a loaner for a few months, so I had the chance to do a little experimenting myself. The upshot is that I’ve always known a lot about eye tracking for someone who doesn’t actually do eye tracking.

And here’s what I know:

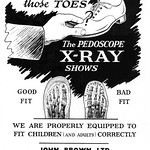

Eye tracking is sexy. Harry Brignull once did a presentation that drew an analogy between eye trackers and the shoe-fitting fluoroscopes that were used in shoe stores from the 1920s to the 1960s.2 Your child would put his or her feet in an opening at the bottom of the machine, and you could peer in and see the bones inside, giving you the comforting knowledge that the shoes weren’t going to warp your child’s tender feet. It was fascinating, it was science (not opinion), and it offered the promise of proof. And it had lots of sizzle.3 Heatmaps have the same kind of sizzle.

It sells. Even though we can all agree in retrospect that the shoe-fitting fluoroscope was probably not a good idea, it sold shoes. And blinding people with science still works: eye trackers sell UX services. You can probably charge more if your deliverables include some heatmaps, whether they show anything that’s useful or not.

It seems easy. But it’s not. It’s no trick nowadays to do some eye tracking and create compelling graphics that make it seem like you’re proving something. But actually knowing what you’re doing takes time, experience, and learning.

It’s hard to learn how to do it well. There have been tons of academic papers and manufacturers’ white papers, but no one has produced a how-to book for practitioners.

Enter Aga.

Actually, I’d like to take a tiny bit of credit for this part. I’d heard Aga speak several times over the years, so I knew that she always had the smartest things to say about eye tracking and UX. Then I read an article she wrote for the UX magazine and discovered that she was a really, really good writer. So I told Lou Rosenfeld he needed to get her to do a how-to book. Now that it’s here, I feel a little like a proud uncle. Or maybe a matchmaker.

Believe me, you’re in good hands. Aga really knows her stuff, and she’ll tell you just what you need to know. This is, as she’s described it, “The book I wish I’d had when I was starting out doing eye tracking.” What more can you ask for?

BTW, if I were an eye tracking manufacturer, I’d buy a few hundred copies and give them away to all my customers and potential customers. And then I’d loan Steve Krug another eye tracker.

—Steve Krug

Author of Don’t Make Me Think

1. The other two are consumer-affordable speech recognition good enough to do accurate dictation (finally happened in the late 1990’s) and reliable lie detection (still “twenty years off”). Curiously, I don’t know of anyone other than me who thinks that effective lie detection would cause greater social disruption than, say, an infinite source of free, clean energy, or anti-gravity boots.↩

2. Harry Brignull’s presentation slides can be found at http://j.mp/eye-tracking-uxlx.↩

3. Probably not literally. No one has tracked down whether anyone suffered ill effects from the radiation.↩