Design.

The word conjures images of effete eccentrics imposing cuboidal-built environments, clashing color, tortured fashion, and over rated celebrity upon the jaded palates of urbanites with too much money.

This book is not about that. Nathan brings the competence of a mechanic, the mind of an engineer, the training of an MBA, and the pen of a poet to a topic long abandoned to people with delusions of adequacy. He talks about solutions, ones that deliver desired outcomes, and how to implement them.

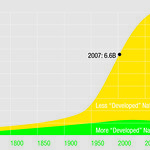

His focus is the design of a world that works; as he says, “Don’t do things today that make tomorrow worse.” Good advice. This book presents a systems approach to crafting answers to the really big challenges, including how to meet human needs on a plan et on which all major ecosystems are in decline, and it’s a race to see which will melt first, the Arctic or the economy.

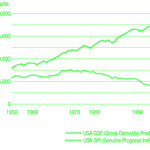

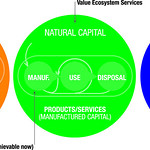

Most of us, if we think about design at all, consider color, or perhaps shape. But reflect that every human artifact was designed by someone. This person made deliberate choices about the utility of the object, the materials used to make it, the manufacturing process chosen, the length of its useful life, and what would happen to it after it was no longer needed. Consciously or by choosing to ignore opportunities, we have created a world in which half a trillion tons of stuff is pulled from the Earth each year, put through various resource crunching activities, shaped (at great energy cost) into a form, and then thrown away. Of all this stuff, less than one percent is still in use six months after sale. All the rest is waste. At the moment of conception of an idea, a design, a thought of a product or a process, 80 to 90 percent of the lifetime cost of that widget, program, or pickup truck was committed.

Investing in how designers think, in how we all approach a new idea, is thus crucial if life as we know it is to thrive on this planet. Nathan has given us the mental model to begin that exploration. He does so with a soft touch, but a ruthless honesty. One of my favorites of his lines is, “Get over the guilt or shock or outrage or embarrassment or disagreement now, because none of it will be useful. We have a lot of work to do.”

It is almost axiomatic that designers are arrogant and indulgent. Nathan is not. He delivers an outstanding primer on the precepts of sustainability, the challenges facing the world, and pragmatic answers in a playful and accessible manner. This book should be part of any curriculum on design, innovation, business, environmental studies, marketing, public policy, engineering, organizational development, and the now rapidly emergent field of sustainability.

It should be on the desk of CEOs of all companies that make or deliver anything. It will be required reading for all of my students, and a frequently recommended treat for the companies with whom I consult. It should be the next book you buy.

—L. Hunter Lovins

Author of Natural Capitalism and Sustainability

Chair, Presidio School of Management